The Athenian Agora Has Gone to the Dogs!

With a paw-sitively delightful new title, we are thrilled to see the revival of the Agora Picture Book series, a collection of well-illustrated thematic guides to the material remains of the Athenian Agora. While birds and horses each featured in earlier publications within this series, now man’s best friend gets its very own treatment. In Dogs in the Athenian Agora, Colin M. Whiting vividly recaptures how the ancient Greeks were just as charmed by dogs as we are today. Whiting distills a trove of textual and material evidence dating from the Archaic period to the present day into a lightweight, accessible volume rife with brilliant color images of dogs that served as pets, hunting companions, deities, and even modern-day tour guides.

With a paw-sitively delightful new title, we are thrilled to see the revival of the Agora Picture Book series, a collection of well-illustrated thematic guides to the material remains of the Athenian Agora. While birds and horses each featured in earlier publications within this series, now man’s best friend gets its very own treatment. In Dogs in the Athenian Agora, Colin M. Whiting vividly recaptures how the ancient Greeks were just as charmed by dogs as we are today. Whiting distills a trove of textual and material evidence dating from the Archaic period to the present day into a lightweight, accessible volume rife with brilliant color images of dogs that served as pets, hunting companions, deities, and even modern-day tour guides.

Realizing that the Agora Picture Book series contained a noticeable—and rectifiable—gap in its treatment of animals in the Agora, Whiting set out to discover what he could about the domestic animals that have become such a pervasive part of modern life. Inspired by his work as project editor for The Agora Bone Well (Hesperia Supplement 50) by Susan I. Rotroff, Maria A. Liston, and Lynn M. Snyder, Whiting took a deep dive into the world of dogs as represented in classical Greek thought. This line of inquiry melded well with another of his research interests, hunting metaphors in late antique literature, yet he acknowledges that “this project was a welcome opportunity to look at dogs and society more synthetically, rather than just looking at the material related to a specific project or text.”

Whiting proudly displaying the culmination of his research on dogs in the Athenian Agora (Photo C. M. Whiting)

During his tenure at the ASCSA Publications Office, as well as his earlier participation in the Regular Member program, Whiting acquired a deep familiarity with the Athenian Agora and the wealth of information unearthed about the site throughout 90 years of ASCSA excavations. In his work on dogs, Whiting found that a focus on the Agora had the advantage of providing rich material evidence while also limiting the scope of his work in a meaningful way. Whiting notes that “there is more in the Agora’s collection than a single piece of pottery or set of remains, but not quite so much that one would need the ambition to write a significantly longer (and denser) book … And, of course, working with material from the Agora comes with many other benefits: friendly and supportive colleagues, excellent recordkeeping going back nearly 100 years, world-class photography, and a meticulous press.”

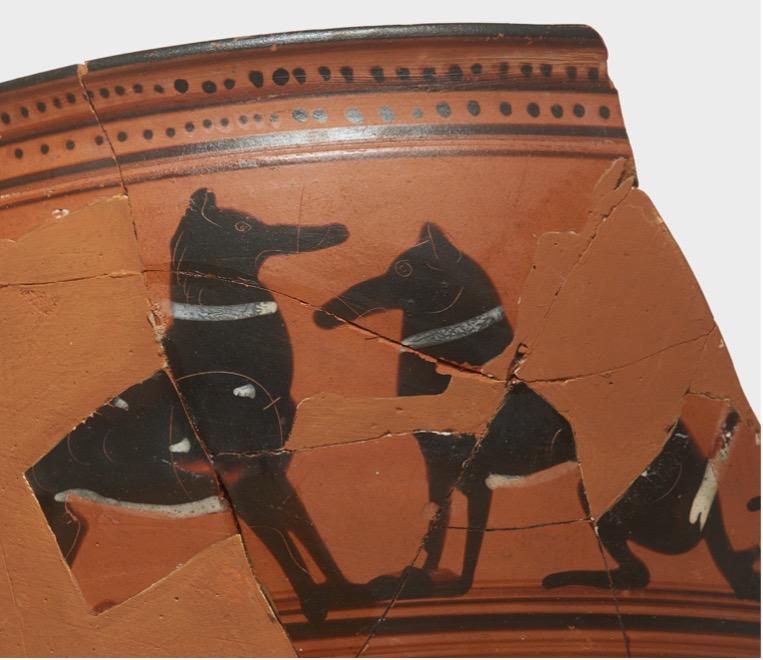

Access to the physical objects and exceptional photographs in the Agora’s collection allowed Whiting, who identifies primarily as a textual historian, to wade into the world of material culture. Ancient literary references to dogs abound, and Whiting declares that “they are pervasive, even if they often lurk in the margins.” But bringing these passages into conversation with archaeological evidence provides a more comprehensive look into a dog’s place in ancient Athenian society. For Whiting, one of the most interesting discoveries was the depiction of dogs wearing collars. He comments, “In hindsight, it’s obvious, of course, that Greeks would put collars on their dogs. How else do you control an animal like that? And from there, it’s obvious that they would then paint collars on dogs depicted on their pottery. But there is something very charming in something so mundane.”

Fragment of black-figure shallow wine cup (skyphos) with hounds wearing collars. Ca. 500 B.C. Agora P 2710 (Photo C. Mauzy)

Fragment of black-figure shallow wine cup (skyphos) with hounds wearing collars. Ca. 500 B.C. Agora P 2710 (Photo C. Mauzy)

Similarly mundane but no less charming are the pawprints left behind on terracotta tiles that had been left to dry in the sun—no doubt to the frustration of the craftspeople who made them! Evidence for ancient dogs took more exceptional forms as well. Beloved lapdogs and hunting hounds were commemorated on various art objects. Dogs also played prestigious roles in mythology, including Kerberos, the canine guardian of the underworld, and Anubis, the jackal-headed deity introduced to Greece from Egypt. Archaeological evidence for dog sacrifices further suggests that these animals held special significance to Greek deities, while serving as a grim reminder that much of ancient Greek religion remains alien to modern mindsets.

Terracotta tile preserving canine footprints. Probably 4th–5th century A.D. Agora A 5193 (Photo C. Mauzy)

Terracotta tile preserving canine footprints. Probably 4th–5th century A.D. Agora A 5193 (Photo C. Mauzy)

Whiting’s book comes at a moment when the field is witnessing a renewed interest in the study of animals in the ancient world. The ASCSA’s current exhibit in the Makriyannis Wing of the Gennadius Library in Athens, “Hippos: The Horse in Ancient Athens,” merges art and science to further our understanding of horses and their role in ancient Greek society. Whiting himself is helping organize a panel on animals in late antiquity slated for the 2024 SCS Annual Meeting. In addition to contributing to the current interest in animals in antiquity, Dogs in the Athenian Agora revives the Agora Picture Book series, which has not seen a new title published in over 15 years. Through this series, scholars have the opportunity not only to expand our general understanding of the Athenian Agora, but to do so in a way that broadens the audience who might engage with this material. As Whiting notes, the books in the Agora Picture Book series “are affordable books of immediate interest to a wide readership, and that becomes more important by the day. The field of Classics is in dire need of greater public engagement; we simply cannot afford to stand by and let other people define what the ancient world means for us today.”

Simple hound figurine. Last quarter of 6th century B.C. Agora T 1815 (Photo C. Mauzy)

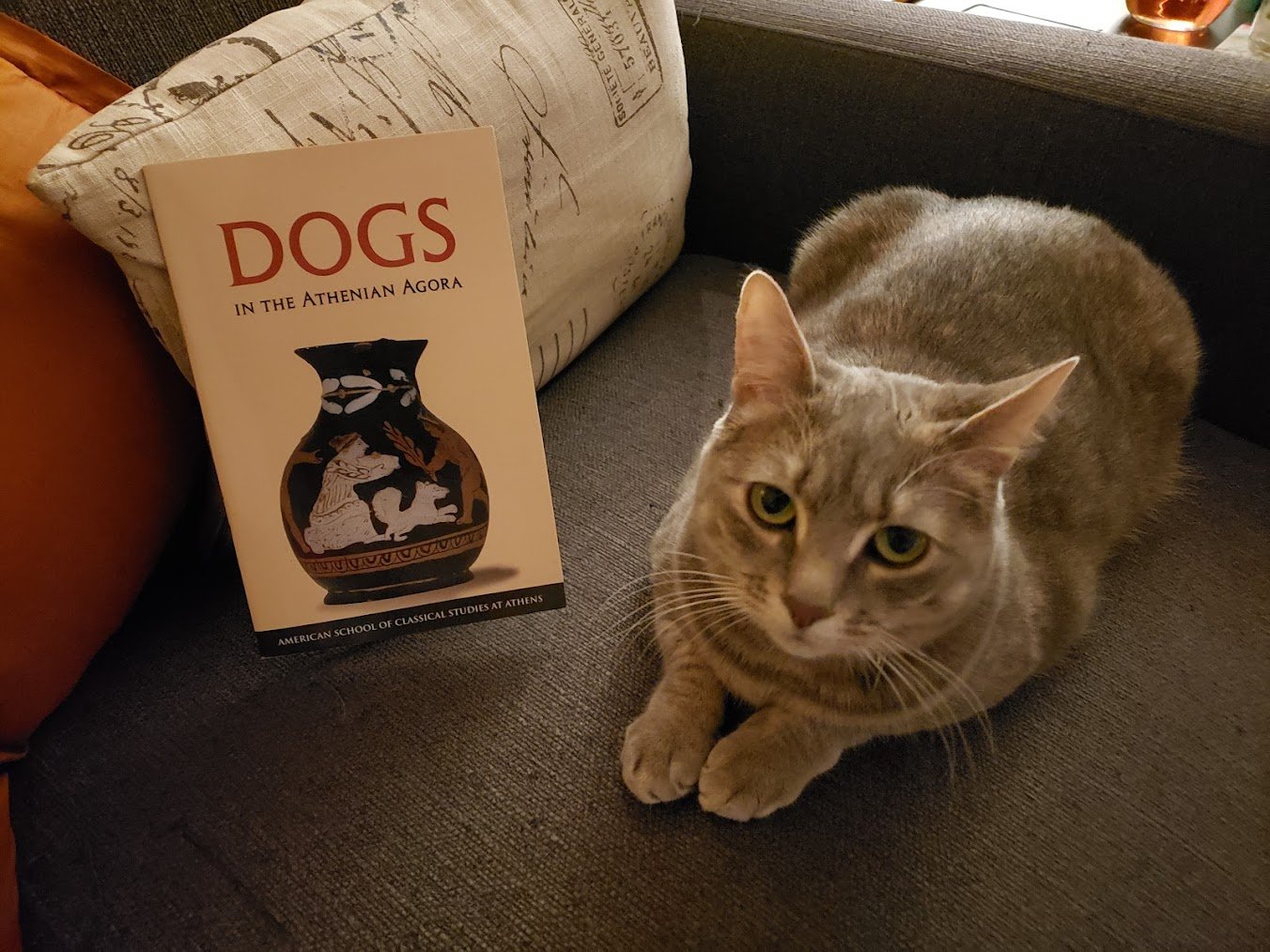

For the cat lovers wondering if Cats in the Athenian Agora will be the next volume in the series, Whiting admits that someone else must take up the banner of such a project. Although the original impetus for Whiting’s research was a book on both cats and dogs in the Agora, cats, unlike their canine counterparts, were not common house pets in ancient Greece. Whiting laments that “the two halves [of the original project] didn’t mesh, so I—with some sadness!—left out the cats.” A book about ancient cats would likely need to expand to felines generally—including lions, panthers, and leopards—and focus much more on their mythological representation than domestic encounters.

Whiting’s cat Moira with Dogs in the Athenian Agora, seemingly bemused as to why cats have not yet gotten their due (Photo C. M. Whiting)

Whiting’s cat Moira with Dogs in the Athenian Agora, seemingly bemused as to why cats have not yet gotten their due (Photo C. M. Whiting)

Anyone interested in animals in antiquity, however, will find much to love in this beautifully illustrated volume. From Maltese lapdogs scampering about the ankles of children to Molossian hounds charging after their prey, Whiting demonstrates how dogs enjoyed a generally comparable place in ancient society as they do today. Dogs are still a present, if fading, aspect of the contemporary Athenian landscape. Anyone who visited the Agora in the 2010s will surely remember Rex shepherding tourists and archaeologists alike through the site. His regal image can be found near the end of Whiting’s book, highlighting the continued presence of dogs in the Agora across time. This view into an intimate part of ancient Greek life also advances our overall understanding of antiquity. With Dogs in the Athenian Agora, Whiting aims to change some common preconceptions about ancient life: “ancient Athens still conjures up images of dour old men pontificating about philosophy while wearing flowy robes. …But I hope this volume shows that sometimes, these dour old men had to hold a dog while it urinated all over their flowy robes. The ancient world was a vibrant one, and I hope this volume gives us a little glimpse at its color.”

Rex surveying his domain in the Athenian Agora in 2013 (Photo C. M. Whiting)

Rex surveying his domain in the Athenian Agora in 2013 (Photo C. M. Whiting)

Dogs in the Athenian Agora (Agora Picture Book 28) can be ordered from our distribution partners: Casemate Academic (in the United States) or Oxbow Books (outside of the United States).