Rediscovering the Julian Basilica: A Conversation with the Authors of Corinth XXII

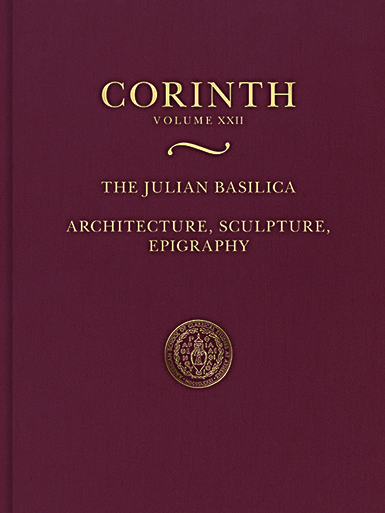

The newest addition to the Corinth series, The Julian Basilica: Architecture, Sculpture, Epigraphy (Corinth XXII), by Paul D. Scotton, Catherine de Grazia Vanderpool, and Carolynn Roncaglia, is the long-awaited and much-needed restudy of the Julian Basilica at Corinth, with the scope extending to the breadth of evidence from the basilica: the architectural, sculptural, and epigraphical remains. Previous volumes in the series, notably Corinth I.5 by Saul Weinberg, have tackled elements from the basilica, but a synthetic approach to the building has not been undertaken until now. Decades after earlier volumes, the authors have identified additional blocks and new joins and mined old field notebooks with fresh eyes.

The newest addition to the Corinth series, The Julian Basilica: Architecture, Sculpture, Epigraphy (Corinth XXII), by Paul D. Scotton, Catherine de Grazia Vanderpool, and Carolynn Roncaglia, is the long-awaited and much-needed restudy of the Julian Basilica at Corinth, with the scope extending to the breadth of evidence from the basilica: the architectural, sculptural, and epigraphical remains. Previous volumes in the series, notably Corinth I.5 by Saul Weinberg, have tackled elements from the basilica, but a synthetic approach to the building has not been undertaken until now. Decades after earlier volumes, the authors have identified additional blocks and new joins and mined old field notebooks with fresh eyes.

Scholarly Beginnings

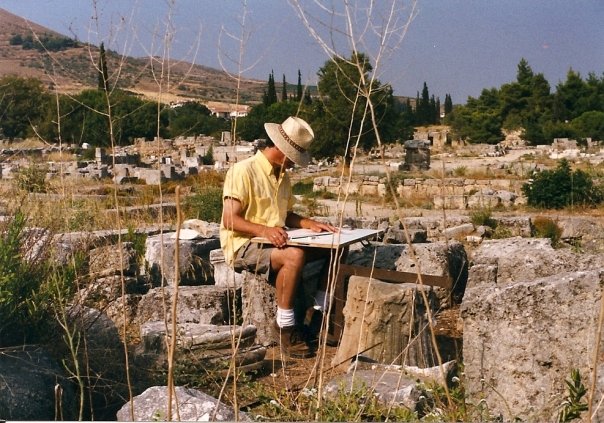

Paul Scotton’s relationship with the Julian Basilica began in 1992 when he was a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania. Following the excavation season at Corinth, he was invited by then Director Charles Williams to reexamine the basilica after blocks that were not attributed to the building in Corinth I.5 had since been identified with it. “At the end of the six-week period,” Scotton remembers, “I had roughed out an elevation of the west facade, a section through the building, and a plan of the main floor, all of which differed from those published in Corinth I.5.” At this point, it was evident that more work needed to be done, and Scotton, who had been trying to settle on a Bronze Age subject for his dissertation, found himself preoccupied with the Julian Basilica. When Williams agreed that he should study the basilica for his dissertation, Scotton and his family moved back to the village that December and settled there for two years.

Scotton draughting a Pergamene capital from the Julian Basilica, 1999 (Photo J. Lavezzi)

The challenges of studying a building excavated in the early 20th century are not few, and the case of the Julian Basilica was especially challenging since the in-situ architectural remains survive no higher than the cryptoporticus. “The placement of everything from the main floor up had to be derived from disiecta membra,” explains Scotton. In addition, the basilica was used as a storage yard for the east end of the Forum, meaning that many objects now housed there were from other buildings at Corinth. Assigning provenance to the various elements at the site required Scotton to revisit notebooks from the original excavations and compare the drawings and descriptions to his own autopsy. “Although the earliest notebooks are far short of our expectations today, by the time the Julian Basilica became the target of intense excavation in 1914, the notebooks of Carl Blegen and Emerson Swift were exemplary,” writes Scotton. “An early frustration, however, was that all that detail was in some regards impenetrable. The location system employed in the notebooks referenced points and objects that are no longer present or extant. One of the most significant discoveries during my work on the basilica was finding Swift’s area plan of the excavations in 1914/1915; it had fallen behind the drawers of a drawing cabinet. This plan proved to be the key to understanding the notebooks, from which I could then determine the findspot of key artifacts and the position of section sketches.”

View of the east aisle of the basilica during excavations, 1914 (Photo Corinth Excavation Archives)

Carolynn Roncaglia’s involvement with the basilica came years later, in 2009 at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America hosted that year in Philadelphia. “Paul Scotton invited me to join this project, and I was excited at the opportunity to work with such a challenging collection of inscriptions, since I knew that many of the inscriptions were quite fragmentary,” she recalls. At the time, she was a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, working to complete her dissertation on northern Italy in the Roman Empire. She remembers thinking that “the Julian Basilica’s inscriptions presented an intriguing chance to examine some of the same processes that I was addressing in my dissertation, but in a Corinthian context.”

One year later, in 2010, Scotton invited Catherine de Grazia Vanderpool to join his study, and the team was assembled. Vanderpool reflects, “Scotton invited me to work on the sculptural material, which embraced not only portraits but also a mélange of fragments spanning centuries of production. Among the hundreds of images from ancient Corinth—some whole, mostly scrappy—those from the basilica stood out for their coherence, their quality, and the fact that their context was better known than most of the sculpted material scattered throughout the city strata until Early Modern times.” But Vanderpool was no stranger to the artifacts from the Julian Basilica, as she had been a student of Corinth’s Roman portrait sculpture since she was a graduate student at Columbia University in the 1970s. “At the suggestion of one of my dissertation advisors, Eve Harrison, and with the consent and encouragement of Charles Williams,” she writes, “I traveled to Greece in 1970 to work on the site’s extensive collection of Roman portrait sculpture in lieu of going to Rome, which is where I really wanted to be.” This decision altered the course of her scholarly career, and “as fate would have it, I was destined to spend my life and career in Greece. The city of Rome was a dream realized fitfully over the years, but always as both background and foreground to my scholarly interests and imagination.”

Previous Work on the Basilica

The authors’ reexamination of the basilica required careful collaboration with the decades of scholarship already published on the material. “My copies of Corinth 1.5 (1960) and VIII.3 (1966) are well worn, well annotated, and stuffed with loose pages of notes, both handwritten and typed,” Scotton remarks. “My digital copies of Corinth VIII.1 (1931) and VIII.2 (1931) do not show the wear, but they have been used just as much, and they are all still within easy reach at my desk.” Roncaglia agrees that “Corinth VIII.1, VIII.2, and VIII.3 became so familiar to me during my study that it felt as if I were in conversation with Meritt, West, and Kent.” By the time Vanderpool began working on sculpture in the 1970s, it had been nearly half a century since the excavation of the basilica, and the most notable sculpture had already been published in the 1920s and 1930s. The material was first treated in a series of incisive essays by Emerson Swift. Franklin Johnson then published the portraits in Corinth IX.1 (1931), along with several articles.

Portrait of Augustus (S-1), which has appeared in many earlier publications on the

Roman portraiture from Corinth (Photo P. Dellatolas)

While earlier publications laid an important foundation for the authors’ reconsideration of the basilica, they also provided an opportunity for departure from previous approaches to the material. “Although at times I came to different conclusions than Weinberg, his work was a great aid to mine,” Scotton notes, and “Meritt, West, and Kent, through their discussions of the inscriptions, helped to make clear one of the primary functions of the basilica: a venue for the imperial cult.” Vanderpool had incorporated the portraits from the basilica into her dissertation, but her approach, she relates, “was more art historical than archaeological, a catalogue raisonné that focused on issues of style and iconography, with heavy emphasis on similarities to or divergences from metropolitan Roman materials. It was a product of the early 1970s, and heavily influenced by Eve Harrison’s work at the Athenian Agora. With a few exceptions, including Harrison’s work, the study of Roman Greece during this time was of less scholarly interest than in more recent years, and less work, particularly of a synthetic nature, had been published.” It was clear that a holistic approach to the basilica site and its remains would significantly augment earlier work on the site as well as provide a model volume for other scholars working on material with similarly rich but fragmented publication histories. “For me,” reveals Vanderpool, “working on the basilica again was a wonderful opportunity to engage, and re-engage, in a significant way with sculptures that I had thought about only sporadically over the intervening years since the 1970s.”

A Fresh Approach

What Corinth XXII offers to decades of scholarly conversation is the value of a synthetic investigation of a building. “Including architecture, sculpture, and inscriptions within a single volume stresses just how important it is to consider the totality of a building and its finds,” Scotton contends. “The three different avenues of investigation lead to discoveries that support and enhance each other within the context of the whole.” The material was difficult due to its fragmentary state, but the authors proved ready to reconsider old excavation notebooks, shelved inscriptions, and generations of new scholarship with fresh eyes.

Fragmentary altar dedicated to Divus Augustus (I-6), with the bottom fragment depicting a rosette

briefly rejoined for a study photograph, 2011 (Photo C. de G. Vanderpool)

“Since the publication of Corinth VIII.3,” Roncaglia notes, “new joins had been made and new fragments found. In addition, a few inscriptions had been lost and quite a few fragments renumbered. Detective work in the old field notebooks helped clear up which fragments were which and offered the best information on inscriptions that had been lost since their discovery.” Detective work is an apt description of the process, as some fragments of inscriptions had even made their way to Athens during World War I. “A particularly satisfying find,” recalls Scotton, “was fragments of inscriptions that had been removed from Corinth for safekeeping during World War I and were returned from the National Archaeological Museum decades later.” Two of the fragments joined and proved to be the beginning of the inscription I-2, a dedication to the Caesares Augusti.

Inscription I-2 (Photo P. Dellatolas)

For Vanderpool, studying a body of sculpture that included pieces with extensive publication pedigrees granted her to the opportunity to “hit the refresh button,” and consider these objects with the “help of several generations of fascinating and new (for me) scholarship,” she writes. These publications were born from “new excavations in Greece, new publications of Greek materials, and the burgeoning interest in Greece under the Roman Empire and in provincial and colonial histories in general. New approaches (or new languages) were used in the study of portraiture, and scholars considered how portraits were manipulated to shape individual, group, and imperial identities, and to frame power and authority.” Ultimately, Vanderpool relates, “It gave me a chance to dive into the field anew.”

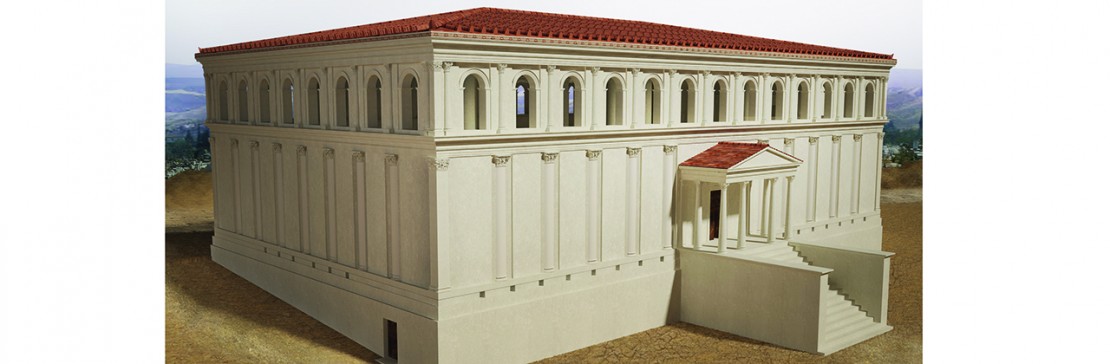

One of the highlights of the volume is several reconstructions of the basilica during its various phases of use. Scotton produced these pen-and-ink drawings himself, illustrating in remarkable detail plans of every feature, including the porches, windows, and ceiling coffers. “Greek and Roman architecture is rational and tends to follow recognized proportions, patterns, and configurations,” explains Scotton. “Accordingly, much can be derived from relatively little; this is especially true for structural elements.” In addition to Scotton’s pen-and-ink reconstructions, the volume provides ten computer-generated color reconstructions of the basilica and its regal interior, created by Scotton’s former student Janet Juarez. “I am a decent draughtsman, but Janet’s renderings, derived from my pen and ink drawings, brought the building to life.”

Decisions about decorative detail proved more of a challenge than the basic architectural reconstruction, but “for both the Augustan and Antonine phases of the basilica, enough is certain to enable reasonable conjecture. The color scheme for the Augustan phase is derived from fragments of painted stucco found in destruction debris near the tribunal. The colors—black, red, yellow, and green—were used in fairly predictable patterns, as demonstrated at several sites, especially Pompeii. While the color choices and placement in our renderings are not certain, what the reader sees in Corinth XXII would not have seemed unusual to the Roman eye.” Far less certain, asserts Scotton is the “design of various marbles and stones. The thickness of a slab is a good indicator of what may have been a paver or revetment, but beyond that there is no design scheme that is easily discernible.”

A reconstruction of the cryptoporticus that did not make the final cut (J. Juarez)

Corinthian Collaboration

The success of the volume is credited not only to its authors’ willingness to work closely with decades of scholarship, field notebooks, and orphaned material, but also with each other. “Paul, Carolynn, and I became a troika,” writes Vanderpool. “We each moved at a speed imposed by personal and professional commitments, so perhaps a little slower than a single-authored volume, but very satisfying. It was a real education for me in early imperial architecture and epigraphy; in the newer work at ancient Corinth, a site that seems to be endlessly rewarding; and in the nuances of intellectual teamwork.” Working at Corinth offers access to the company and support of seasoned excavators and scholars. For Roncaglia, this was her first time studying Corinthian material, and she “was struck by just how welcoming and generous both the scholarly community and people of Old Corinth were.” Scotton too felt “privileged to have been welcomed into the academic environment created by Charles Williams and Nancy Bookidis. The intellectual stimulation and comradery were second to none.”

Vanderpool in Rome, where she “always wanted to be,” 2022 (Photo C. de G. Vanderpool)

During their collective years spent at Corinth, the authors remember fondly their time on site and in the village. “I often worked in the upper storeroom in the Old Museum, where I could see visitors walking past the Julian Basilica and Fountain of Peirene,” Roncaglia recalls. “Watching the religious services held by tourists on site was very moving and reminded me of Corinth’s enduring significance.” Vanderpool, like Roncaglia, needed to devote in-person time to the objects she was publishing. “With the teachings of Eve Harrison and Bruni Ridgway very much in mind, I never forgot that at the basis of sculptural publication is the object, which deserves careful autopsy and description before one can launch into the ‘fun part,’” she relates. “So, I spent some happy times at ancient Corinth in the apotheke and museum revisiting old friends.”

During the two years that Scotton and his family lived in the village, he remembers “attending the equivalent of PTA meetings at the local school, name-day parties, weddings, and funerals.” These experiences assimilated his family to village life such that “Corinth truly is our second home.” Although his daughters were quite young when they lived there, “they have vivid memories of Corinth and still remember the many times that they tossed a small sack of bougatsa over the fence and down to me while I worked in the basilica below.”

Future Endeavors

As for other projects, the authors have a full agenda, but it does not stray far afield of Corinth. Scotton divides his time between co-directing excavations of the Lechaion Harbor and Settlement Land Project, a synergasia between the ASCSA and the Corinthian Ephorate of Antiquities, and a future monograph on Corinth’s Southeast Building, yet another nod to the legacy of Weinberg’s Corinth I.5.

Vanderpool intends to publish other Roman portraits from Corinth. “I have in mind a synthetic work about the portraiture of Julius Caesar, based on the extensive numismatic record both from his lifetime and thereafter,” she reveals. “As always, I will start with the object, using it to explore how the Romans deployed human images, male and female, to express profound and desirable societal values, to define normative behaviors, and to identify and establish authority.” She considers ancient portraiture a powerful weapon in the “Roman arsenal of non-lethal means of imposing empire.”

Roncaglia may have returned to her original scholarly focus, Italy, but her work on Corinthian material has had a lasting impact. “My current project,” she hints, “appropriately lies geographically between northern Italy and Corinth.” No doubt the publication of Corinth XXII will have a lasting impact beyond Corinth too, as it sheds light on how imperial and local power intersected at a particular ancient site. The Julian Basilica, as Roncaglia concludes, “was where the elites of Corinth and the provincial governor presented a vertically integrated system of imperial power.”

The Julian Basilica: Architecture, Sculpture, Epigraphy (Corinth XXII) may be ordered from our distribution partners: Casemate Academic (in the United States) or Oxbow Books (outside of the United States).