Notes from Naxos

Hello All - we’re Evan and Rebecca, both 2019-2020 student members at the ASCSA. We work on landscape survey and Greek sculpture, respectively, and this week we are undertaking some new research on Naxos which combines our diverse specializations.

Because of the decision to stay in Athens when the strict lockdown began in March and the unfortunate but necessary cancellation of our normal summer commitments, we now have the unique opportunity to be working in the (mostly empty) field this summer. For those who might be far away and missing Greece, we will be sending some updates from the Cyclades back to Athens and North America so that others can follow along. Please join us!

PART 1

At 'home' in Athens (Agora Excavations)

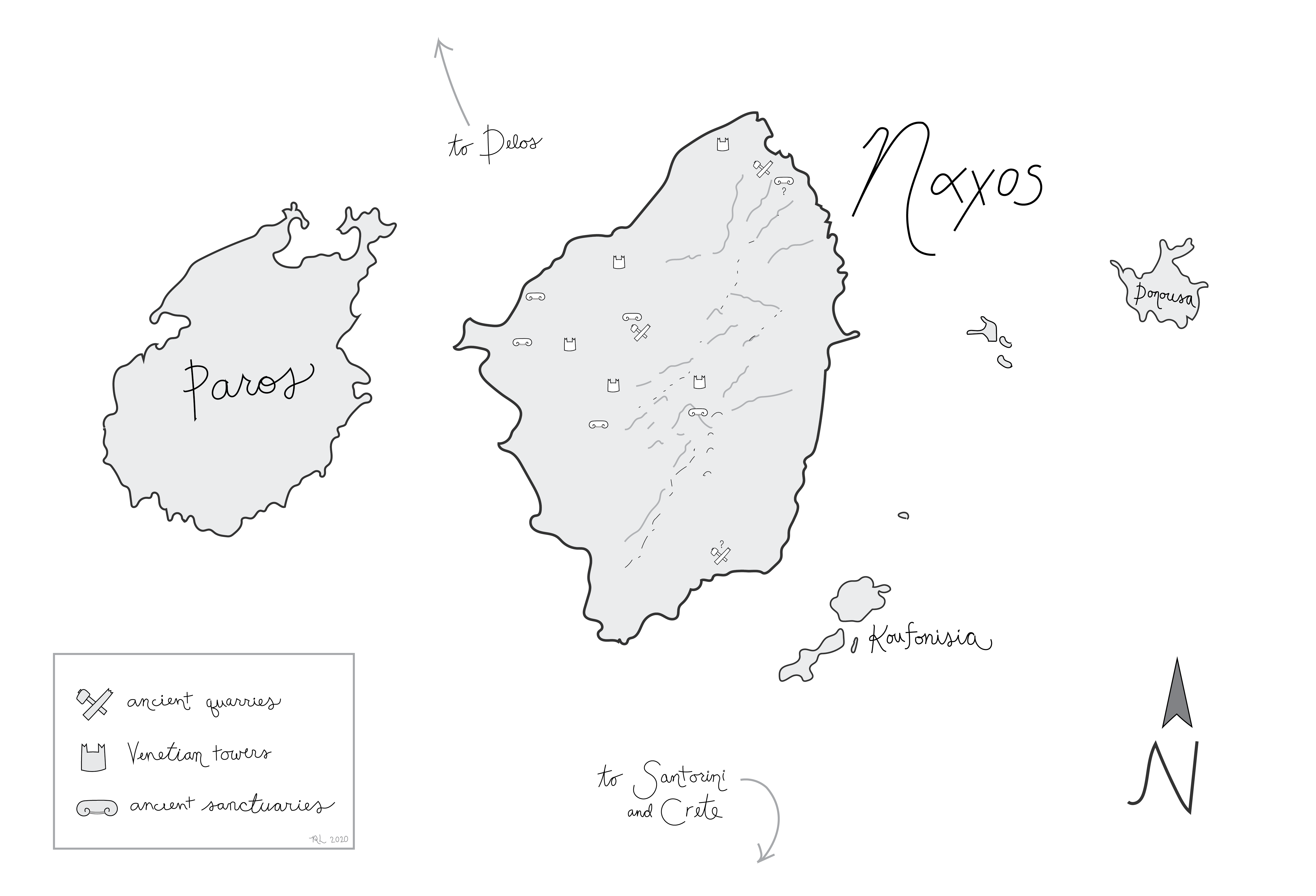

Our project centers on the ancient quarries of Naxos, which were the source for many of the most well-known architectural and sculptural monuments of Archaic Greece, including famous dedications at Delphi and Delos. By studying marble monuments that never left the island, or in some cases, the quarry, we hope to gain a better understanding of the techniques and motivations of Naxian patrons and craftsmen and situate ancient quarrying within the larger island landscape.

Because of our different training and backgrounds, we are deploying a range of tools, techniques, and documentation styles over the course of the week. This includes the analog (tape measures, drawing in pencil) and the digital (photogrammetric modeling, mapping and analysis in GIS, and digital illustration). We also wanted to informally record our time on the island, including these ‘Notes from Naxos!’

Getting acquainted with the older inhabitants of Melanes quarries.

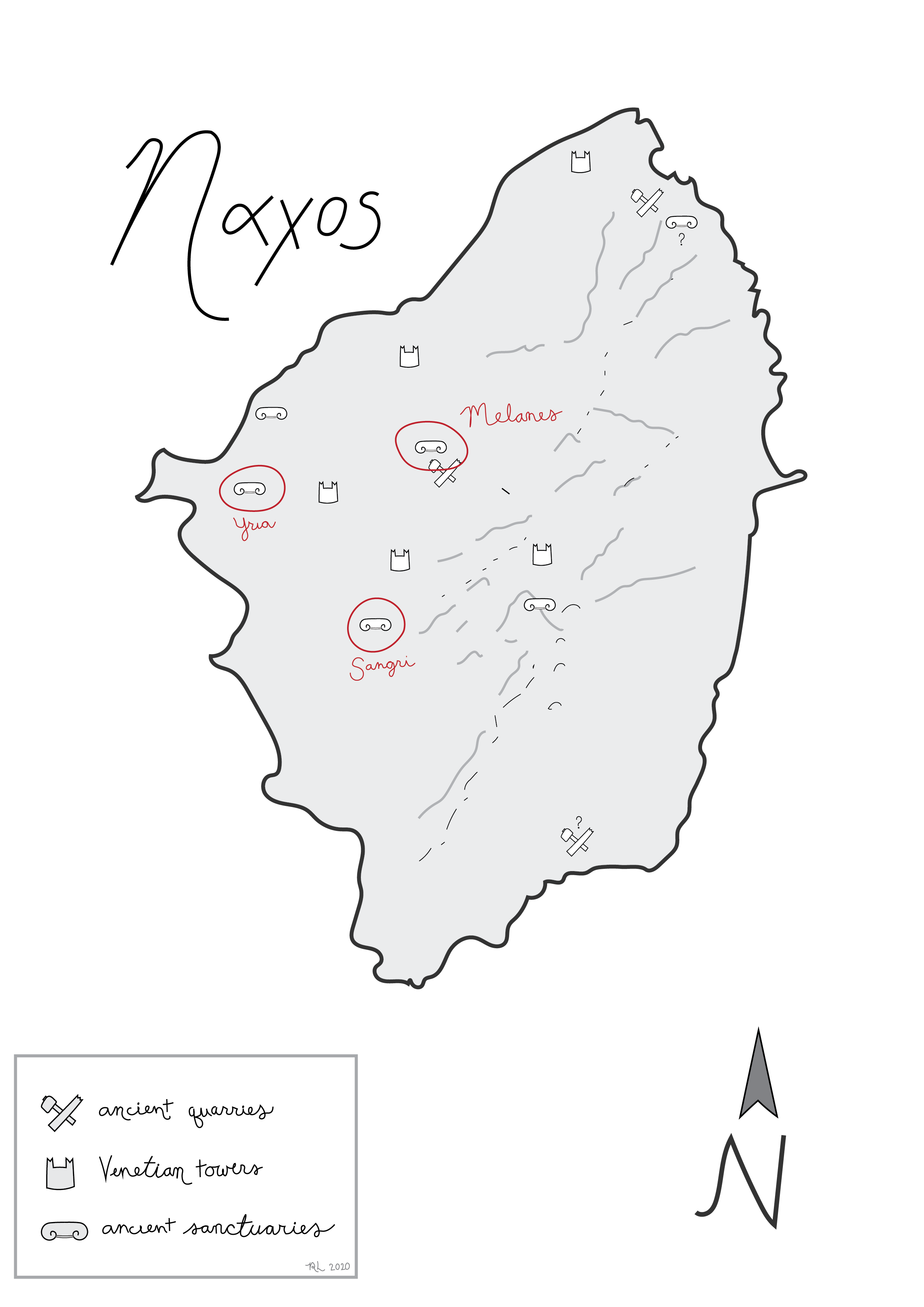

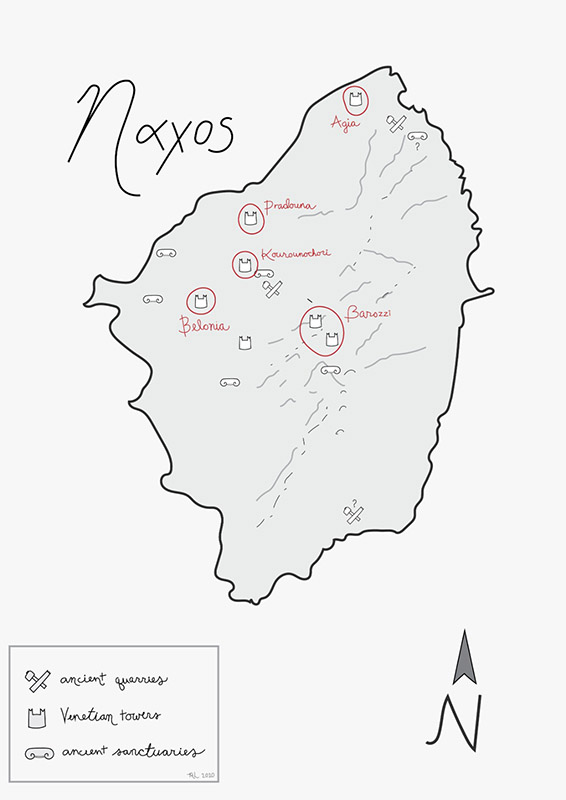

As the week progresses and we get our bearings, Rebecca will be adding to our ‘Notes from Naxos’ map:

The locations and further information about sanctuaries, towers, and quarries are available through these links (in google maps).

And for those who might be more familiar with the archaeology, history, and extensive bibliography of Naxos - we welcome your suggestions!

You can also follow along with us on twitter (@LevineRx, @LevintheMed). Evan has been writing daily threads this week for Tweeting Historians (@Tweetistorian).

Some light reading in Melanes Village

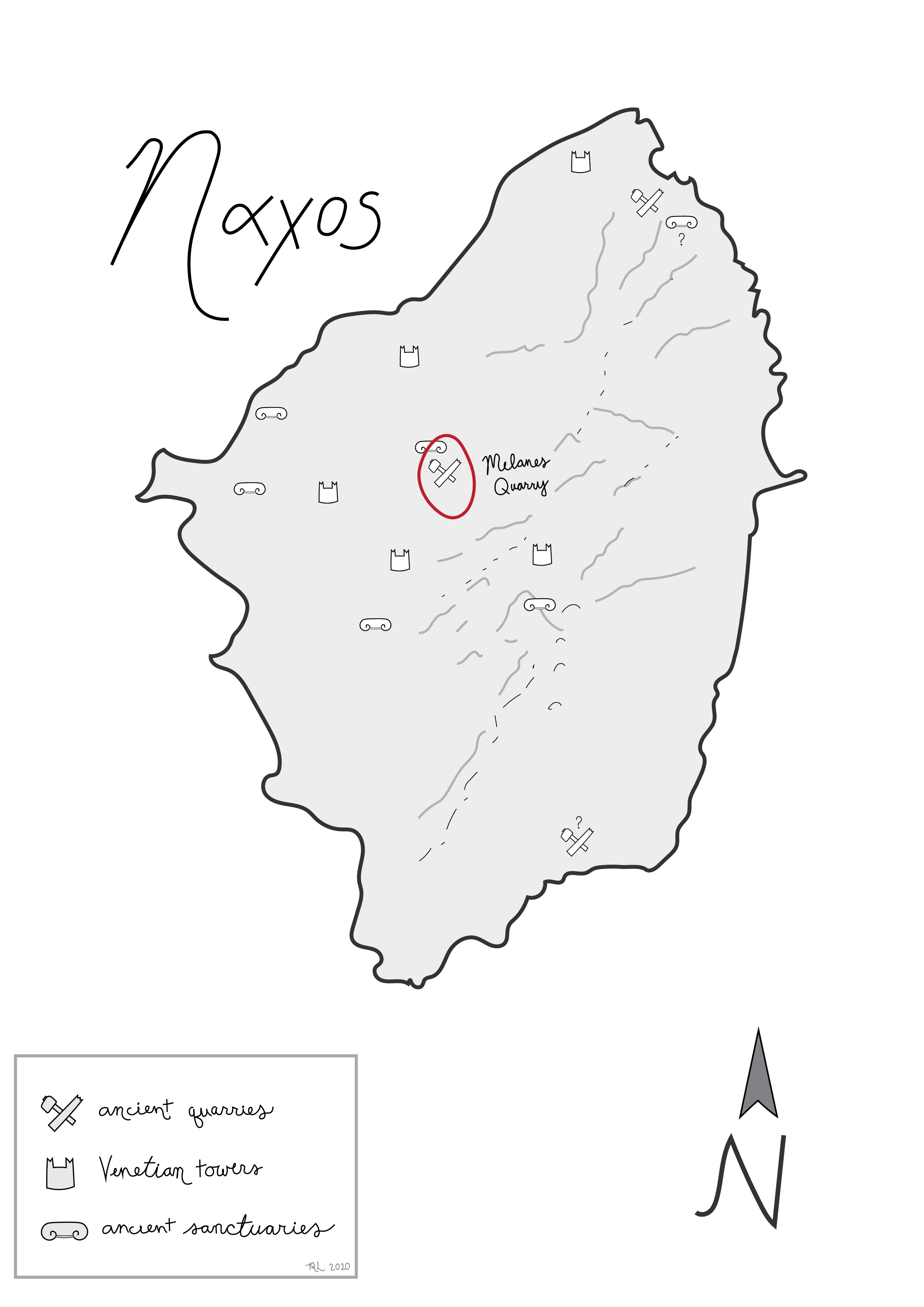

PART 2 - Melanes Archaic Quarry

Naxos was well-known in antiquity for agricultural and geological exports including fine crystalline marble and emery - a hard stone used as an abrasive in stone carving. Even today, the island is still a major exporter of marble and emery and the landscape is punctuated by modern quarries - but the ancient ones are a little tougher to spot...

Modern Quarry en route to Kinidaros

As we mentioned in our last note, we are exploring all the ancient quarries of Naxos, but our research began at Melanes - the most prominent Archaic Quarry, which was the source for many major dedications. We can begin to get a sense of the extraction process from studying the remains of ancient quarrying activity which are still visible in the area, as well as the two ancient Kouroi which were abandoned shortly after their extraction - likely from flaws in the marble or accidents that happened in the early stages of transportation.

Evan tries not to fly a drone into the tree

protecting the lower Melanes Kouros

Our day began by meeting Michalis, a guard from the Ephoreia and Naxos Museum at the site of Flerio/Melanes. In addition to the extensive ancient quarries, the site also includes a sanctuary and an archaic aqueduct with Roman renovations. All three were investigated by a team from the University of Athens in a major project which ended in 2010..

The modern road which leads to the lower kouros is actually built on top of a small flowing river which would have been essential for the ancient use of the quarry. It was here that the roughed out blocks began their journey to the sea, where they could then be transported to sanctuaries in the western part of the island or, more famously, to other parts of Greece, including Panhellenic sanctuaries. This river was likely larger in antiquity, but still irrigates many of the farms nearby, including the orchard where the lower kouros now rests.

The University of Athens team acquired the area immediately around the first abandoned kouros of Melanes, so it now lies in a walled-in enclosure which includes a very large tree. This tree provides lovely shade and also protects the kouros, toolmarks are still visible in many places. We were able to note these and document them with handheld cameras. However, the shady location made it very difficult for us to document the kouros on a larger sce because the tree's canopy prevented us from flying the drone over the statue. However, Evan was still able to set up his RTK base - a sort of portable total station which allows for the collection of very accurate geophysical data - and take some points which could then be used to scale and georectify our photographs.

The first kouros is remarkable for a number of reasons. The most striking initially is the scale - it stands (or really, lays) at 5.57 meters. Another is the degree to which the quarrymen and sculptors had already defined the form of the figure - presumably removing as much excess marble as possible to lighten the weight of the kouros before transit.

After some refreshment of water and donuts kindly provided by Michalis, we made our way with our equipment up to the second, higher, kouros. Although a bit more of a hike, and therefore less accessible for tourists and visitors, the location of the second kouros in a relatively open field below a rocky outcrop was preferable for our documentation because we could more easily measure its dimensions and photograph it within its larger quarry context using the drone. The open field also made it easier to "shoot in" the location of the kouros with the RTK base and rover, since they did not need to communicate through a tree.

Emlid Reach RTK in action at Melanes

However, the second kouros' location has its downsides: the surface of the unfinished sculpture is currently suffering from environmental deterioration. The Kouros is also more severely cracked and missing its feet - which lay nearby. The preserved height is still impressive at 4.12m.

Documenting the higher Kouros with handheld cameras, and in our notebook.

We noticed many small worked fragments in the vicinity, which were scattered in the area around the kouros and built into low rubble walls. We documented each of these fragments to make more sense of them through 3d modeling and integrate them into our larger study of the quarry. Extensive survey across the outcrop above revealed extensive quarrying, including toolmarks, trenches, wedge cuttings, and evidence of some suspiciously kouros-sized blocks!

Rebecca tests dimensions of a missing block,

in the Melanes quarry bed.

PART 3 Sanctuaries

The Sanctuary at Sangri and surrounding agriculture

After spending our first two research days documenting the unfinished kouroi in the ancient quarries of Melanes, we then spent the next part of our time on Naxos focusing on an important output of the Melanes Quarries: the archaic sanctuaries of the island which featured architecture in Naxian marble.

One difficulty in studying ancient quarries stems from the anonymity of the people who worked there. These populations certainly included enslaved and free skilled craftsmen, but of course no details about who they were are recorded in our literary sources. However, Quarries can provide evidence for the quarrymen’s handiwork and techniques, and in the case of Melanes, archaeology can also provide some clues about their religious practices. In the early 2000s a sanctuary was excavated near the quarries at Melanes that demonstrates both long lasting religious practice and direct links to quarry activities.

Archaeologists from the University of Athens led by V. Lambrinoudakis recovered evidence of cult activity from as early as the Mycenaean period at this unusual circular sanctuary anchored by large boulders, now known as ‘The Sanctuary of the Source’. The circular orientation was renovated continuously from the 8th century onward. However, it reached its height and received a marble temple in the Archaic period, when the quarrying nearby was also moving at full speed.

Evan at Sanctuary of the Source at Melanes, Naxos

An inscription nearby identifies the site as a sanctuary dedicated to Otos and Ephialtes, the mythical brothers described by Homer (Odyssey 11.305-325). These sons of Iphimedia and Poseidon were both giants who were able to move mountains - certainly appropriate figures of worship if you’re in the rock-moving business. Many of the votive dedications found at the sanctuary are unfinished sculptures from the nearby quarry - including a small unfinished kouros. Another unfinished dedication is a roughed-out marble sphinx which is reminiscent of the shape of the colossal Naxian dedication at Delphi. The excavation of the ‘Sanctuary of the Source’ site is published, and there’s even a preliminary report which links findings from the sanctuary to the Oikos of the Naxians on Delos, which you can read in English here.

An unfinished marble Sphinx,, perhaps dedicated by a quarryman who worked nearby?

It is not hard to imagine how quarrymen worked with architects to build the Sanctuary of the Source, which itself lays in a marble outcrop. But what about the other major archaic sanctuaries of Naxos, which are also built of Melanes marble? We see similar collaboration between the stonecutter and architect at the temple of Dionysus at Yria and Demeter at Sangri. Both are early examples of temples which are built nearly entirely from marble.

An early example of the architectural use of Melanes marble can be found about 10km west of the quarry at the marshy Dionysus sanctuary at Yria. It makes sense that the Naxians would pull out all the stops for this sanctuary, Naxos is the island of Dionysus after all! The site is located near the Byblinis River (said to be wine rather than water) is still a place of productive vine cultivation today. The sanctuary was supposedly located at the spot where Dionysus found the abandoned Cretan Princess Ariadne. (She had, of course, been left by Theseus on his way back to Athens after killing the Minotaur.) In the early sixth century, four buildings were added to the Geometric sanctuary, including an innovative temple featuring a very early use of the Ionic order. We were able to view fragments of a few of these columns at the small museum on site. A monumental gate marked the entrance to the sanctuary, flanked by dining rooms for ritual feasting.

The archaic Ionic Dionysus temple at Yria, Naxos

Melanes marble can also be spotted at the archaic sanctuary of Demeter at Sangri built around 530 BC and located 11 km southwest of the quarry. In addition to its all-marble construction, the temple at Sangri has a number of unusual and curious architectural features, including a nearly-square plan and a south-facing facade with two entrances framed by five columns. A partial restoration in 2001 by a team from the Universities of Athens and Munich highlights the columns, which along with the roof featured unusual entasis. When we arrived at the site, there were no other visitors, but there was still plenty of activity happening around, as it is surrounded by productive farms - only appropriate for Demeter!

The unusual Demeter temple at Sangri, Naxos

Part 4 Towers

We spent the first half of our trip researching archaic quarrying at the ancient site of Melanes (Read More) and the sanctuaries that were built out of its marble (Read More)

Aside from abandoned megaliths and excavated sanctuaries, Naxos’ varied history means that much of the evidence for ancient architecture is actually found embedded in the buildings of later periods. Perhaps most notable are the many fortified Venetian towers, castles, and manor houses which are scattered across the landscape and exist in various states of preservation.

Ancient blocks can be spotted in the construction of the Belonia Tower, built before 1610.

While driving to Melanes, Sangri, and Yria, we passed several of these structures which were hard to miss. These towers were in various states of repair, some on the verge of collapse, while others have been converted into museums or continue to function as homes. In fact, we discovered that the tower closest to the Melanes quarry in the village of Kouronichori is for sale! While we waited for our next research appointment at the Apollonas Quarries we decided to investigate the history of these towers a bit more, and learn about their varied fates.

This tower-home, built between 1371 and 1383 could be yours! Includes historical features such as a marble table from 1727 and zematistres (slots for pouring boiling oil on your enemies).

The Venetian presence on the island dates to the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade (1199 – 1204), when adventurer, sailor, and aristocrat Marco Sanudo sailed a small fleet from Constantinople to conquer Genoese-controlled Naxos. Upon arrival, he burned his fleet and laid siege to the mountaintop stronghold of Apaliros. Sanudo took the island after a four months siege and set about solidifying Venetian control across the Cyclades. Naxos became the seat of the Duchy of the Aegean with centuries of fascinating history, filled with political maneuvering, intrigue, and plenty of pirating.

|

|

|

The Barozzi-Gratsia tower, which includes a wooden drawbridge, was built in the village of Halki in 1690

Sanudo and his family ruled Naxos for nearly two hundred years, and were responsible for building the giant castro complex which now dominates Naxos Chora. When Sanudo’s descendent Nicolo dalle Carceri was assassinated in 1383, a new family - the Crispi dynasty - came into power and continued to rule until 1537 when the pirate Barbarossa and his Turkish fleet took the island. The settlement of the island today still reflects the Venetian era of occupation on the island; the largest villages sit in the mountains, at Chalki, Filoti, and Apareinthos, which each center around at least one Venetian tower. The immense Venetian Castro in Naxos Chora testifies to the anxiety of a vulnerable port.

|

|

One of the oldest standing towers on the island, the Barozzi pyrgos in the mountain village of Filoti was built in 1650.

Aerial and satellite imagery reveal that modern Naxian agriculture and settlement are still guided by the island’s Medieval past.

|

|

The abandoned Pratsouna tower near Eggares village is located in a lowland agricultural valley. It is now abandoned.

Roughly thirty stone pyrgi or towers are found on Naxos, most of which date to the 1600s, when the island was under constant threat by pirate raids. We were only able to visit a small fraction on our trip - highlighted here:

The Venetian towers are carefully positioned to exploit the natural resources of the island and to solidify Venetian control of the island’s population. The towers are architecturally similar, built from stone rubble (and sometimes spoliated blocks). They generally have a square plan, small doors and windows, ample storage space for produce, and rich living spaces for the island’s elite. Their roofs and chimneys are marked by characteristic horned crenellations.

|

|

Evan explores the Agia Tower, which stands 200m above the island’s Northern coast.

Although they resemble the defensive fortified towers with their crenelated roofs, some of the Venetian ‘pyrgi’ of Naxos are actually fortified manors. These are often centered around agricultural production, rather than strategic locations for visibility. Nevertheless, they served as conspicuous reminders of the status of the elite families. In order to enable tax collection, the Ottomans allowed the Venetian lords and their feudal castles to remain in place - albeit in a much weaker fashion. The island was officially incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1579, but very little effort was made to convert local inhabitants.

Instead, it was the Jesuits, Capuchins, and Oursulins who built monasteries across the island in the 17th century. The massive abandoned monastery at Kalamitsia was constructed in 1673 on the ruins of a Venetian mansion.

The abandoned monastery at Kalamitsia includes vaulted storage, a large paved dining room with flagstones, and many external buildings including a chapel and dovecote.

Other Venetian towers that had fallen into disrepair were reused as industrial or agricultural spaces by local inhabitants.

19th century press inside of the Aghia Tower complex

Part 5: Apollonas Quarry

In the final two days of our time on Naxos, our focus shifted back to ancient quarry sites and archaic sculpture. This time we headed north from the inland quarries at Melanes to the small coastal fishing village of Apollonas.

A sign welcomes visitors to the fishing village of Apollonas

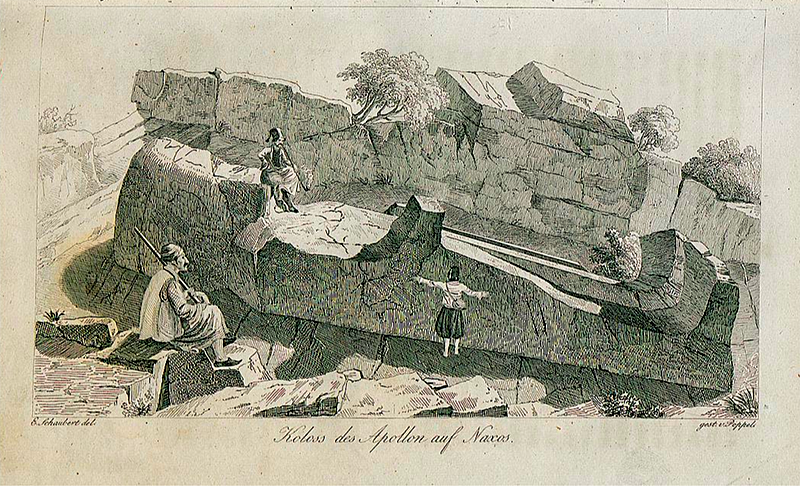

Apollonas village gets its name from a 4th century BC inscription which reads ΟΡΟΣ ΧΟΡΙΟΥ ΙΕΡΟΥ ΑΠΟΛΛΟΝΟΣ (IG XII 5,43). Spotted by travelers to Naxos as early as the 15th century, the inscription was recorded again in 1835 by Ludwig Ross, who explained how the name eventually came to encompass both the ancient quarry and nearby area.

19th century visitors to the ‘Kouros.’ 1835 Illustration by Eduard Schaubert, published in Ludwig Ross’ 1840 ‘Reisen auf den griechischen Inseln des ägäischen Meeres’

Apollonas quarry is home to perhaps the most famous ‘resident’ of Naxos - a 10.7 meter marble bearded figure who permanently reclines in a carved hollow in the marble outcrop. The colossus is the largest megalithic statue produced by the ancient Greeks (depending on where you draw the line between sculpture and prepared stone block).

Evan and the ‘Kouros of Naxos’

Although the monolith was successfully removed from the bedrock, roughly shaped, and lowered about a meter downhill, the project of creating the massive sculpture was never completed. This may have been due to the discovery of critical faults or damage to the marble.

Kouros from above with slope

A gap between the shaped block’s original and current location shows that it was moved several feet down the slope of Apollonas quarry before abandonment.

Alternatively, the act of moving the huge block may have proved to be too difficult or arduous. Unlike Melanes, the marble bedding at Apollonas runs at a slope of nearly thirty degrees and there is no river or stream to help the ancient quarrymen transport the heavy block the five hundred meter distance to the sea.

Rebecca makes the most of the extreme angle of the Apollonas Kourous, sliding down the front to recover an errant tape measure.

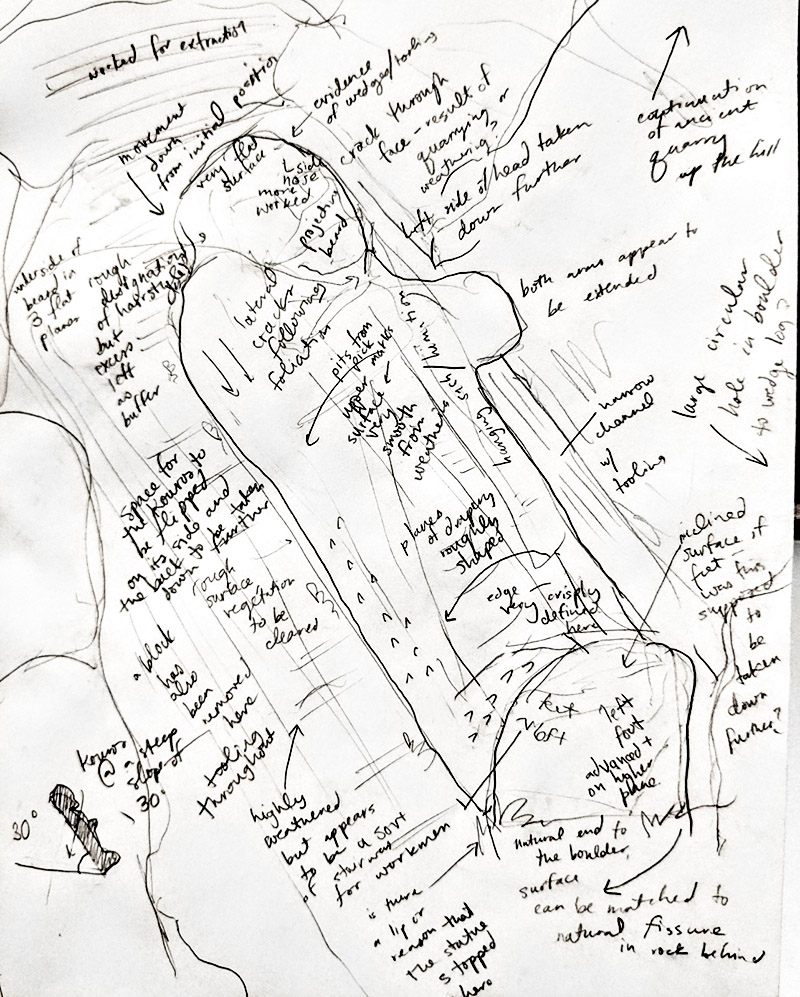

Identifying why the statue was abandoned in the archaic period (whether for logistical or political reasons) was one of our major research goals and planned our strategy for thoroughly documenting the quarry with this question in mind.

Although less extensive than the marble outcrops at the quarry at Melanes, the Apollonas quarry is also characterized by exposed marble boulders interspersed with schist. Thus, we employed some of the same techniques at Melanes, such as close observation, as well as handheld and drone photography.

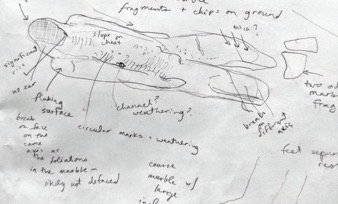

As usual, our research process began with a close observation of the statue and its context in the Apollonas Quarry, as seen in this page from Rebecca’s notebook.

Because stoneworking activity stretches far beyond the massive ‘kouros’ and was executed at a much larger scale (and a steeper angle) than at Melanes, the ability to precisely geolocate the colossus within the quarry using the DGPS units was critical.

|

|

Portable DGPS units were used to precisely locate the statue within the quarry

One of our other research questions centered on the identity of the enormous figure. The nearby presence of the Apollo inscription, an advanced left foot, and similarities with the archaic kouroi from the Melanes quarry led to the sculpture’s early identification as Apollo and title of the ‘Kouros of Naxos.’

However, the abandoned unfinished colossus may not be a ‘kouros’ at all. Although only roughed out, it is clear that the figure is bearded and wears a long draped garment. This led scholars to the current identification as Dionysus, the patron god of the island. Zeus, who was worshipped at a sanctuary on Mount Zas, has also been suggested as a possible subject. However, because the quarrying and carving of this statue was never completed, the date and identity of the enormous figure remain unknown and contested. After evaluating the context of the quarry in relation to the coast and sanctuaries on the island, we have our own thoughts - but you’ll have to stay tuned for those!

Amidst all these unknowns, one thing is certain: even among the many impressive Naxian monuments scattered across Greece, the staggering size of the Apollonas colossus makes it exceptional.

A view of the Apollonas Quarry with humans (1.75, 1.9m) for scale

Final Notes

We hope you’ve enjoyed this journey around Naxos! As we continue to work on this material, we welcome any thoughts on archaic quarries, colossal sculpture, or Cycladic landscapes. Feel free to get in touch!

For those who would like to keep exploring:

Our next stops are Antiparos and Paros, where we will be working on the Small Cycladic Islands Project (SCIP) run by the Ephorate of Antiquities for the Cyclades, the Norwegian institute at Athens and Carleton College. You can read more about the survey here, and follow along on twitter (@NorwInst).

Thanks for exploring with us! Τα λέμε!