Makriyannis’s Paintings for the Greek War of Independence

The Makriyannis paintings are an important treasure of the Gennadius Library and a symbol of Joannes Gennadius’s contribution to the study of Greek history. The paintings give us the opportunity to revisit the worldviews of General Makriyannis, who in the 200 years that separate us from the Greek Revolution has been portrayed by historians as a radical warrior, a revolutionary, a patriot, and a demagogue.

Considering history as a debt to the next generation, Makriyannis learned to read and write in 1829 in order to compose his memoirs. He also made use of the power of the image to capture the immediacy of the historical moment and to awaken in his audience the emotion and enthusiasm of the War.

He first commissioned the paintings from a European painter, who must have worked in the court of King Otto. The individualized elements of western style used by the "Frankish" painter, however, did not correspond to the general perceptions of the general, nor did they capture the collective element of the Greek Revolution. Instead, he chose a Greek fighter, Dimitrios Zografos from the village of Vordonia in Laconia, who, as his surname shows, probably had a painting workshop.

To present the whole truth, Makriyannis visited the battlefields with Dimitrios Zografos and made sketches that explained the events in detail. Moreover, the extensive legend in the lower margin of each image contains many explanatory details, some of which come from Makriyannis's Memoirs.

For Makriyannis, the purpose of the images was "to capture the historical truth and to counteract other false stories," so the illustration had to speak first of all to his soul. It had to match some part of his inner self and of the Greek painting tradition, i.e. the legacy of Byzantine painting. Zographos created the original series for Makriyannis on wood where he used the traditional technique of Byzantine hagiography, the egg tempera.

The naive style borrows types and motifs from post-Byzantine and popular models echoing the simple, uneducated writing of Makriyannis. The eloquent immediacy of the narrative offers the beholder a holistic bird’s eye view with bright colors, lack of perspective, and emphasis on rhythmic movement. It focuses on the collective and non-individual dimension, emphasizing the overall impression and pulse of the battle. It captures the well-known saying of Makriyannis: “We are in the ‘we’ and not in the ‘I’.”

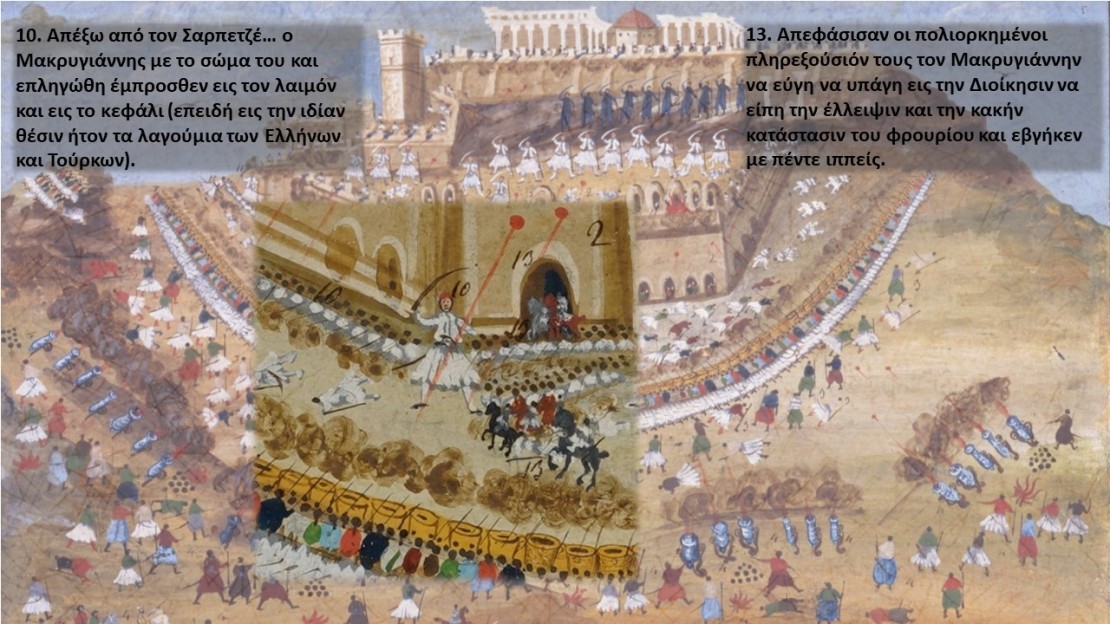

The art of Zographos presents the entirety of individual events that have happened at various points in time in a continuous form resembling a comic strip. The immediacy of the narrative is truly powerful. The painting of the second siege of the Acropolis shown above is literally pulsating. People run, fight, succumb to their injuries, brandish their yataghans, fall. The absence of perspective and the structure of the space as a continuous sloping plane, where the cohesive element is the soil of the sacred rock of the Acropolis topped by the Parthenon including the Ottoman mosque within it, creates a sense of movement and emphasizes the chaos of the battle.

We see Makriyannis himself in the painting; his patriotism and bravery are duly emphasized in the legend. We read: “10. Outside Sarpetze … Makriyannis was hit in front of the neck and the head,” and “13. The besieged decided to send Makriyannis outside the castle as an envoy to go to the Government and tell them about the lack of provisions and the dire situation of the castle; and he came out with five horsemen.” It is worth mentioning, nevertheless, that even Makriyannis, the main hero in this version of the event, does not differ from those around him except for his size and the number that identifies him (10).

After completing the 24 paintings for Makriyiannis in 1836-1839, Dimitrios Zografos made on paper four copies of the whole series in watercolor that were donated as a sign of gratitude to the kings who helped the independence of Greece (those of England, France and Russia) and the king of Greece Otto. Until 1909 only the watercolors sent to Queen Victoria of England in 1839 were known.

In the spring of 1909, Joannes Gennadius bought at auction in Rome the 24 paintings that had been made for Otto. With the donation of Gennadius's collection to the American School in 1926, these impressive paintings reached the Gennadius Library where they are held in trust for the Greek people. They have been used widely as emblematic depictions of the history of ‘21 seen from a Greek perspective in contrast to the paintings of Bavarian and French painters that idealized the history of the Greek War of Independence. The fate of the French and Russian series remains unknown.