Finding Great Value in Empty Graves

The latest volume in the ASCSA’s Lerna series is Michael Lindblom’s The Shaft Graves and Other Late Helladic I and II Remains (Lerna X), which presents the funerary and domestic remains from a pivotal period at this important prehistoric site on the Gulf of Argos excavated by the School in the 1950s. Stratigraphic analysis of the site’s two disturbed shaft graves and surrounding remains contextualizes the ceramics and miscellaneous objects recorded in the book’s accompanying catalogues. While publication of intact monumental tombs often focuses on the elite occupants and their precious grave goods, the value of the Lerna shaft graves lies in what they reveal about the hundreds of living participants in the funerary rituals. Now busy with projects at Malthi and Kalaureia, as well as teaching at Uppsala University, Lindblom recently took time to discuss his work on the Lerna shaft graves and their significance.

The latest volume in the ASCSA’s Lerna series is Michael Lindblom’s The Shaft Graves and Other Late Helladic I and II Remains (Lerna X), which presents the funerary and domestic remains from a pivotal period at this important prehistoric site on the Gulf of Argos excavated by the School in the 1950s. Stratigraphic analysis of the site’s two disturbed shaft graves and surrounding remains contextualizes the ceramics and miscellaneous objects recorded in the book’s accompanying catalogues. While publication of intact monumental tombs often focuses on the elite occupants and their precious grave goods, the value of the Lerna shaft graves lies in what they reveal about the hundreds of living participants in the funerary rituals. Now busy with projects at Malthi and Kalaureia, as well as teaching at Uppsala University, Lindblom recently took time to discuss his work on the Lerna shaft graves and their significance.

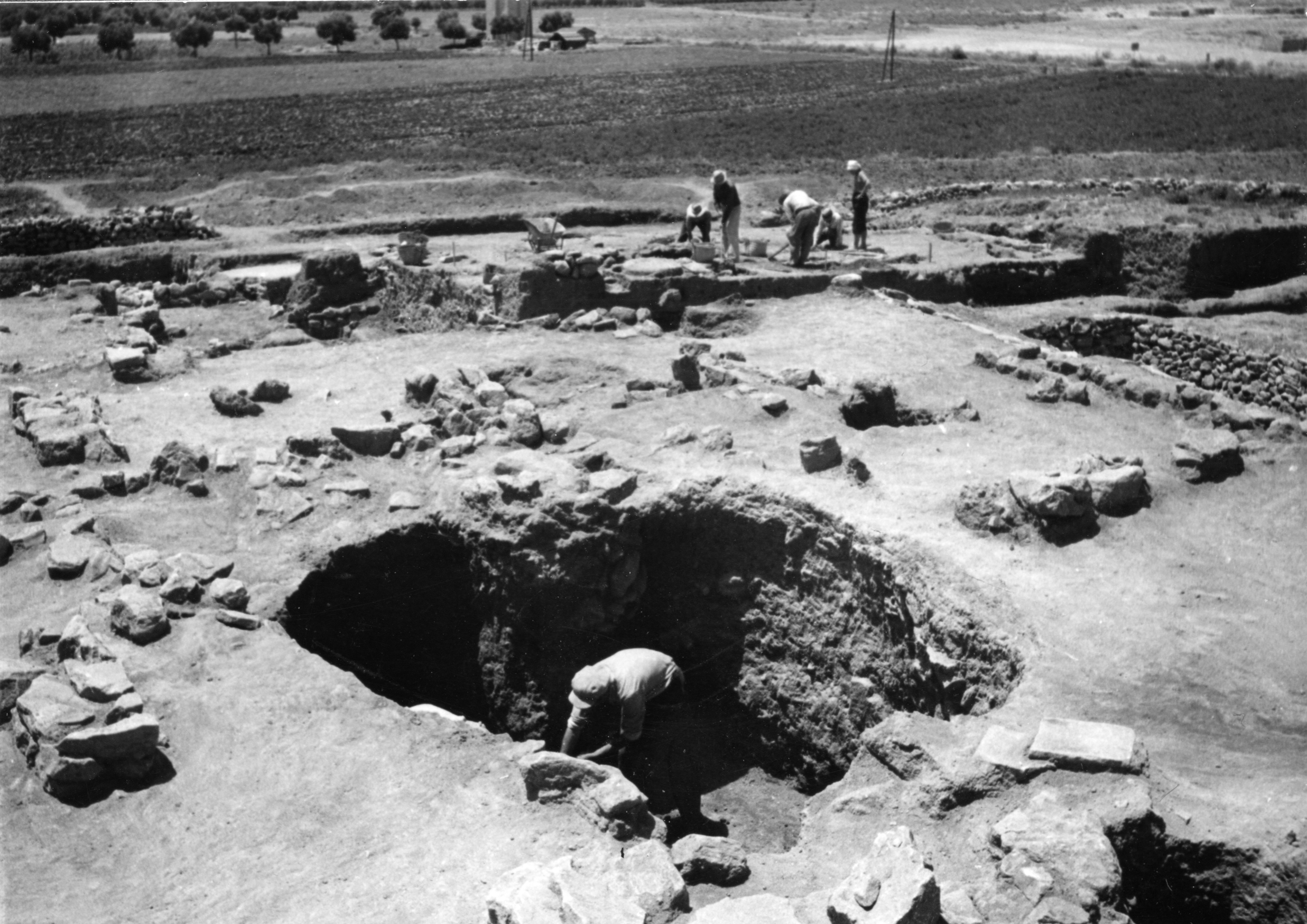

Excavation of the fill of Shaft Grave 2 on June 8, 1955

When asked about what led him to publish a body of ceramic material excavated in the 1950s, Lindblom began by recounting his path to becoming a pottery specialist. He embarked on his Ph.D. work without a concrete plan of study—unthinkable in Sweden today, he notes—but he gained insight into various field methodologies through participation in several excavations in Greece. He remembers developing a fascination with the way “new data, on the surface often chaotic and random, upon analysis turns into patterns that reflect past practices.” Ceramics, he learned, “could be used to discuss consumption practices on various levels. These, in turn, could be fitted into a larger understanding of social organization and, on a higher level of abstraction, even state-formation processes.” Particularly formative was his participation in the Austrian excavations at Bronze Age Kolonna on Aigina from the late 1990s onward. He recalls a memorable afternoon at a café near the site when Jeremy Rutter suggested that he write his dissertation on potters’ marks on vessels produced at Middle and Late Helladic Kolonna—what purpose was served by those inconspicuous signs made before the vessels were fired? Lindblom was excited by the idea, having seen such marks while working with the Asine Collection in Uppsala as an undergraduate. At Rutter’s suggestion, he contacted Carol Zerner, who had identified many potters’ marks among the ceramics she was studying from Lerna. Zerner invited Lindblom to study the Lerna material and even served as an external reader on his dissertation committee. When Zerner decided to relinquish publication rights of the Early Mycenaean remains from the settlement in the early 2000s and Lindblom was asked to take on the project, “I simply could not resist the challenge,” he recalls.

The early days of the project that would become Lerna X were memorable ones for Lindblom. He recounts his efforts to bring “modern” technology to the field:

I bought my first digital camera and scanner for the Lerna project in 2003. The one-megapixel camera on a small tripod coupled with two lamps from IKEA constituted an improvised photo studio that allowed me to photograph all sherds digitally. In the evenings, I inked my line drawings and scanned them on the 600 dpi scanner. Nowadays we consider this equipment antique, but I remember how high-tech and clever I felt at the time.

Lindblom and his wife, Erika Weiberg, at work in the Lerna apotheke in 2004

He also remembers good company in the Lerna apotheke, including his wife, Erika Weiberg, who drafted about half of the profile drawings in Lerna X, and Elizabeth Banks, the author of Lerna VI and VII. Known for her sharp tongue, Banks shared stories and gossip from days of the original excavations at Lerna, enlivening the experience of scholars studying the artifacts and notebooks decades later. Among these scholars was David Reese, who rediscovered animal bones from the shaft grave fills that were thought to be lost. Reese’s analysis of these remains would ultimately appear as an appendix in Lerna X. But there were also long periods where Lindblom worked alone in the apotheke, and he remembers one such day vividly: “On an excruciatingly hot day (118º F), I fell asleep at my table with sherds all around me. When the ephor came for an unannounced visit, I woke up—and my paper form had stuck to my forehead because of the sweat. I literally had to tear the paper from my face before seeing the person standing in the doorway, and I must have made a less than dignified appearance.”

After study seasons at Lerna from 2003 to 2006, Lindblom expected to complete the project quickly. But, as he writes candidly in the preface to Lerna X, work on other projects soon intervened, sometimes dictated by available funding and employment opportunities. When asked why he felt it important to write openly about his academic journey, including times when he nearly left academia before this study was completed, Lindblom replied that he constantly reminds himself “how privileged I am to have a job that I love, and that things might be very different.” Acknowledging with empathy the amount of talent, stubbornness, and luck needed to succeed in academia today—and the toll exacted by the contingent nature of many positions—he exhorts his peers: “As senior scholars with tenure, let’s never forget how frail the life situation of young academics is and do whatever we can to help.” He wanted to share his own story in his preface in part as a tribute to the many colleagues and students he has seen over the decades who wanted to continue their work but did not have the resources to do so.

Teaching and mentorship are important parts of Lindblom’s work; here he teaches Early Helladic pottery classification to Uppsala University students using the Asine Collection

Although the Lerna project was on the back burner after 2006, many of Lindblom’s intervening projects were fruitful collaborations that ultimately enriched his analysis of the Lerna pottery and its significance. One such project was a year-long endeavor to make finds and documentation from Swedish excavations in Greece accessible. Among the tasks was an inventory of 5,000 boxes of predominantly Bronze Age pottery from the 1926 excavation at Asine, now stored at Uppsala University, which Lindblom had already encountered in his undergraduate days. Sorting through this vast amount of material alongside his former supervisor, Gullög Nordquist, provided an intensive lesson in “what the prehistoric pottery across the gulf from Lerna looked like.”

Lindblom displays loomweights from the now well-organized and accessible Asine Collection (Photo P. Blomqvist)

Some of Lindblom’s other collaborations have had an even more direct impact on the conclusions presented in Lerna X, notably work on radiocarbon dating with Sturt Manning and petrographic and chemical analysis with Ian Whitbread and Hans Mommsen, all of whom are contributors to the volume along with Reese. Lindblom relishes working closely with colleagues with different expertise, noting that he has “learned immensely over the years from being able to ask those really stupid questions that many of us carry around but do not have the opportunity to ask, or to test ideas before they go into print.” He remembers how immediately interested Manning was when he first showed him the close ceramic parallels between the Lerna shaft graves and mainland imports in the Akrotiri volcanic destruction level, and the thrill they both shared when the results of the radiocarbon analysis came in. This analysis corroborated the suspicion that Shaft Grave 1 is slightly older than Shaft Grave 2. Similarly, Whitbread and Mommsen, who have unsurpassed knowledge of the various pottery fabrics and chemical signatures present at Lerna throughout prehistory, strengthened the conclusions Lindblom could draw from his own analysis of the Late Helladic (LH) pottery. “Together,” he notes, “I think we make a strong case that the first locally produced Mycenaean decorated pottery was produced in a workshop in the vicinity of Lerna that functioned only for a relatively short period of time in LH I–IIA.”

Whitbread and Mommsen also contributed their expertise to Lindsay Spencer’s recent volume on the Middle Helladic (MH) pottery from Lerna (Lerna IX), such that readers can compare their analyses across the MH–LH transition. The publication of Lindblom’s volume so closely on the heels of Spencer’s is a boon to scholars interested in this transition into the Early Mycenaean era at Lerna. “Although Lindsay and I use slightly different terminologies,” Lindblom notes, “readers will hopefully be able to follow the development of different ceramic classes and consumption practices at the same settlement for over half a millennium.” From the less extensively excavated Early Mycenean settlement, the two shaft graves stand out for their potential to elucidate social and political dynamics within the community. Lindblom explains:

Located at the outskirts of the contemporary settlement, the shaft graves testify to the political aspirations of one or two kin groups and, just like their more famous counterparts at Mycenae, should be understood as physical manifestations of an ongoing dialogue about changing values. I know this sounds rather abstract, so let me try to explain what I mean. The mortuary record generally suggests a rather limited repertoire of parameters to articulate and elaborate personhood. Most burials were unassuming in their material expressions and were probably attended by only a few people. The remains from the shaft grave fills, by contrast, reveal that the organizers of these particular burials were staging events unprecedented in the display and use of resources. This extraordinary behavior was probably only accepted and embraced by other people because of the simultaneous appeal to values that were familiar to them, like the sharing of food and drinks together in other rituals. By participating in a shaft grave funeral, guests were thus happily fueling a spiral of resource concentrations directed toward aims decided by someone else. It is often forgotten that aggrandizing behavior needs an audience, and, unlike the situation at Mycenae and Pylos, in the Lerna shaft grave fills we see the tangible remains from the feasts that entertained hundreds of guests.

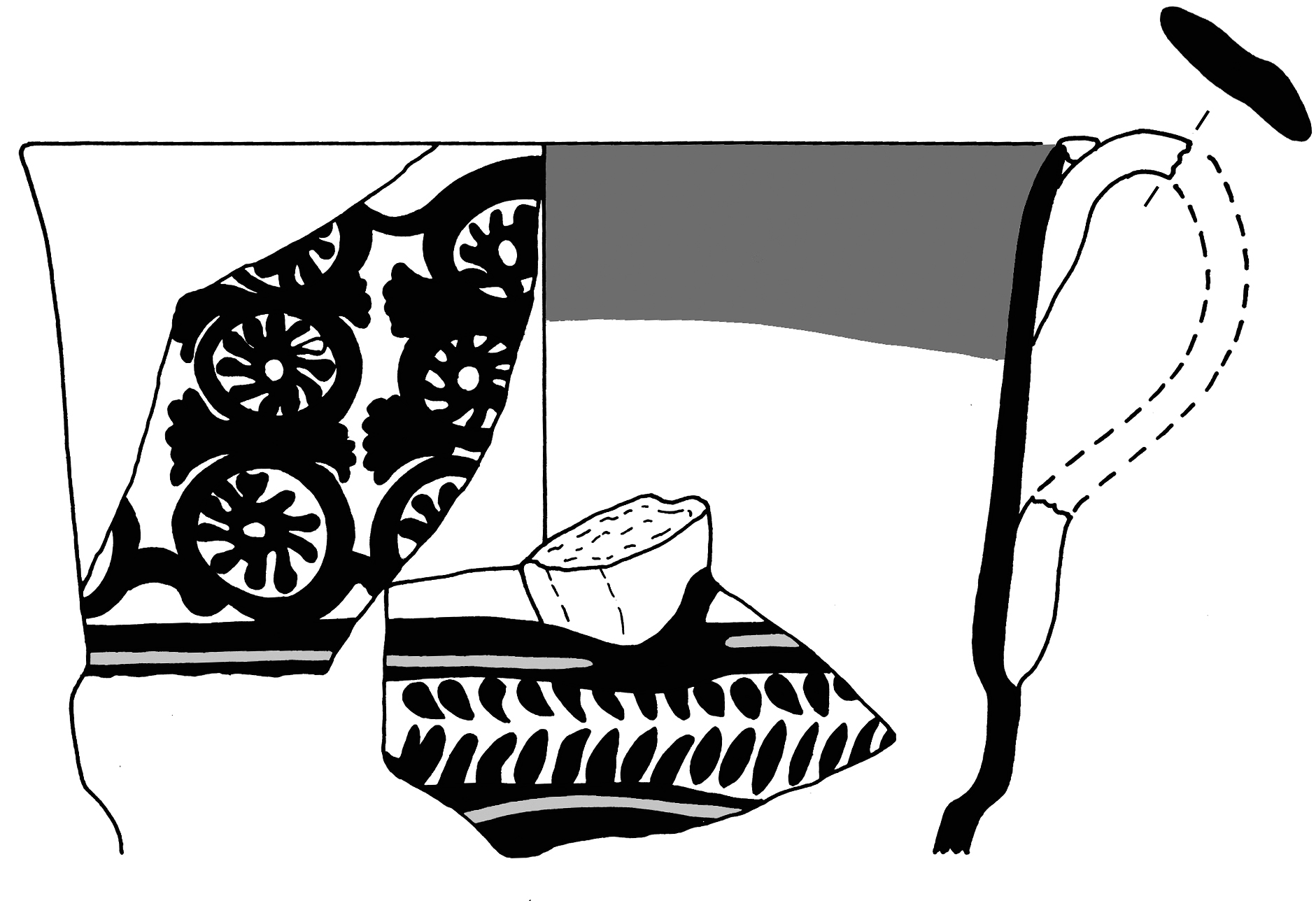

Large Vapheio cup in the lustrous decorated Mycenaean class (P732) with a diameter of ca. 19 cm

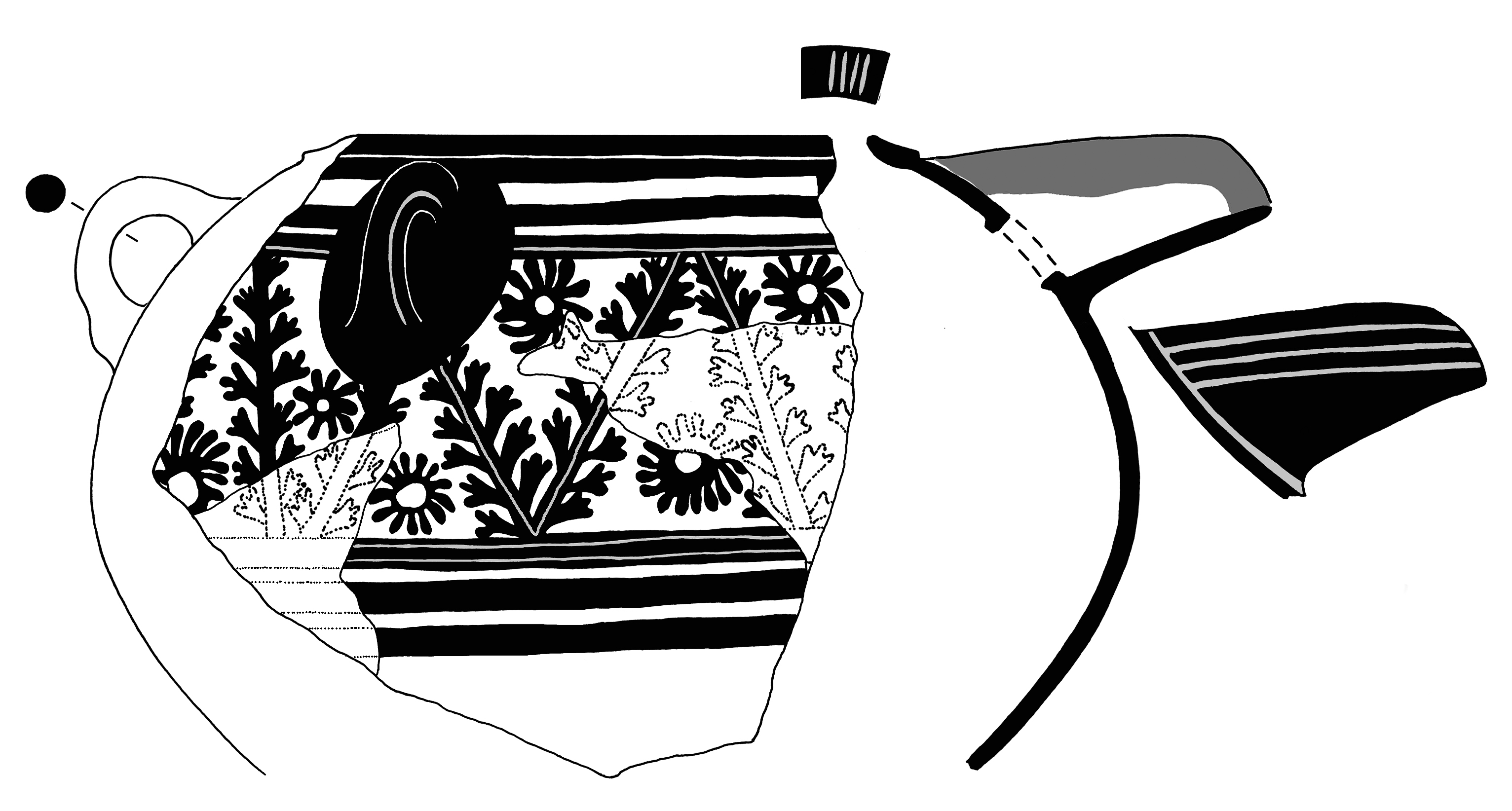

When asked to reflect on his work with the shaft grave assemblage, Lindblom recalls how privileged he felt to handle the material, which included an unusually high percentage of beautifully decorated tableware used in the funerary feasts. He singles out a gigantic Vapheio cup (P732) and a bridge-spouted jar (P733), both decorated with sea urchins and probably intended as a set. “I never have—and probably never will again—worked with such aesthetically pleasing ceramics,” he notes. Even more thrilling was the chronological homogeneity of the material: “Over one thousand vessels were sealed inside the shafts during a few decades around the Late Minoan IA volcanic eruption on Santorini. With the establishment of such a firm datum line,” he explains, “new possibilities to synchronize various ceramic deposits in the Aegean are available for future scholars.”

Bridge-spouted jar in the lustrous decorated Mycenaean class (P733) featuring sea urchins

In Lerna X, Lindblom has succeeded in what he acknowledges to be a difficult task: “publishing archaeological remains faithfully while simultaneously fitting the results into some kind of wider understanding.” His aim has been to produce a book that will appeal not only to those interested in pottery, but also to those who take an interest in the formative stage of what we identify as Mycenaean. He paints a vivid picture of the circumstances surrounding the shaft grave burials at Lerna:

For a brief period towards the end of the LH I period, some families at coastal Lerna apparently resisted the political hegemony at contemporary Mycenae by hosting funerals preserved for the highest elite residing there. They could do so by virtue of their excellent marine networks, which included contacts with the large settlements at Kastri on Kythera and, in particular, Kolonna on Aigina. In hindsight, we know that this attempt was futile. In my opinion, it is possible or even likely that the empty and largely destroyed shaft grave chambers at Lerna are the result of a hostile raiding party coming from Mycenae to thwart such ambitions within only weeks or months of the last interment.

Lindblom excavating with students at the fortified hilltop settlement of Malthi in northern Messenia, 2017

With his work at Lerna complete, Lindblom is now returning his attention to Malthi, a MH III–LH IIB hilltop settlement in northern Messenia. Between 2015 and 2017, he co-directed fieldwork with Rebecca Worsham to clarify the chronology of the Malthi settlement and fortification wall uncovered in Swedish excavations of the 1920s and 1930s. From Malthi he will embark on a new project investigating the remains of a small and only partially explored LH IIIC Early settlement within the later Sanctuary of Poseidon on Kalaureia in the Saronic Gulf. We eagerly await the human histories Lindblom will weave from the pottery and other remains of these sites, just as he has done for the participants in the shaft grave funerals at Lerna.

Lindblom within the LH IIIC Early house uncovered within the later Sanctuary of Poseidon on Kalaureia in 2010–2011

The Shaft Graves and Other Late Helladic I and II Remains (Lerna X) can be ordered from our distribution partner, ISD.