Students and Friends Name Evelyn B. Harrison Room in New Student Center

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens is pleased to announce a gift from the Students and Friends of Evelyn Byrd Harrison in support of the renovated Student Center. The Evelyn B. Harrison Room, located on the second floor of Loring Hall, is named in honor of the distinguished art historian and teacher whose long association with the School spanned more than sixty years.

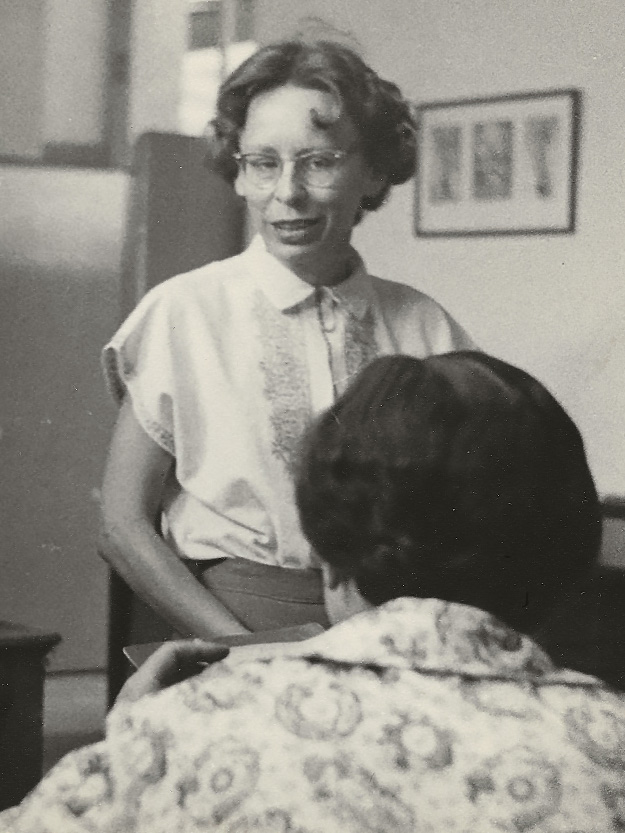

| Evelyn Harrison lecturing during her term as the School’s Whitehead Professor, 1991 (photo courtesy of ASCSA Archives) |

Evelyn (Eve) Harrison (1920–2012) was one of the preeminent scholars of Greek art in the second half of the 20th century. She first went to Greece as a Regular Member of the American School in 1948, supported by a scholarship from the American Association of University Women. The following year, as a Fulbright Fellow, she joined the staff of the Agora Excavations, beginning a long association that lasted until her death. There, on the strength of recommendations from her teachers William Bell Dinsmoor and Rhys Carpenter and in spite of her youth, she was charged by Lucy Talcott with developing and refining the system for cataloging the many (mostly small and worn) fragments of sculpture being excavated annually in the Agora. In a mere two years, she made significant headway on the cataloging project and also wrote her dissertation on the Roman portraits from the Agora, material that had been assigned to her by Homer Thompson but with which she had had little prior experience. She would subsequently spend almost every summer at the School, studying the material from the Agora, the Acropolis and wherever else her scholarly investigations led, and becoming an internationally recognized expert in the process. Although her research took her from the Daedalic to the Early Christian period and occasionally outside Athens, the major thrust of her efforts and her abiding love was for the high Classical period in the city which became her adopted home. In addition to her long list of publications, Harrison devoted herself to a teaching career that extended for 55 years, successively at the University of Cincinnati, Columbia, Princeton, and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. In 1992, the Archaeological Institute of America awarded her its Gold Medal for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement.

George Orfanakos, Executive Director of the School, responded as follows: “On behalf of the American School, I want to express our heartfelt gratitude to the Students and Friends of Evelyn Harrison for honoring one of the School’s most distinguished scholars and teachers. Future generations who pass by the Evelyn B. Harrison Room will learn about this giant of the American School and will be inspired by her example.”

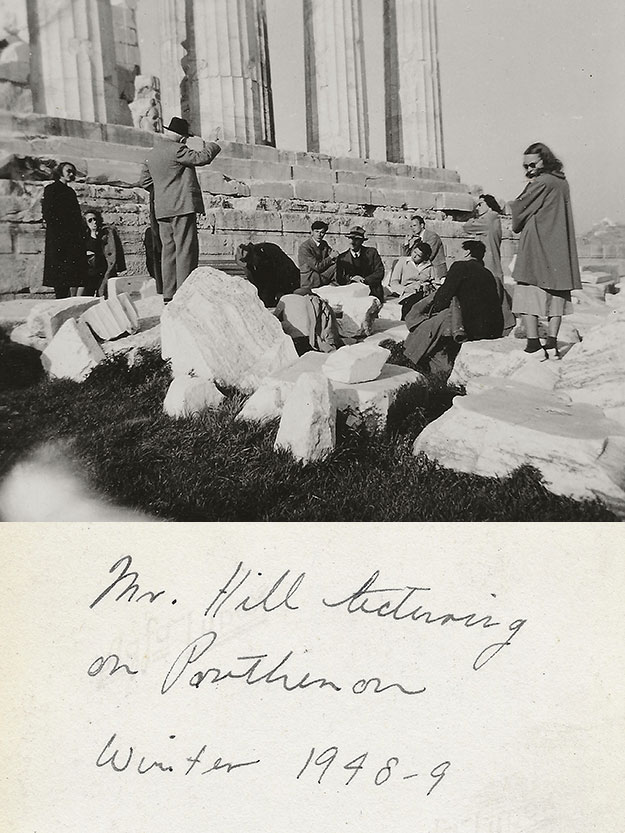

| Top: Eve Harrison (far right) at one of Bert Hodge Hill’s lectures at the Parthenon, winter 1948–1949 (photo courtesy of Evelyn B. Harrison Photo Collection) Bottom: Harrison’s handwritten note on the back of the photo |

Harrison’s students and friends offered the following tribute in her memory:

For more than sixty years, Evelyn Harrison was an integral member of the American School. Her association with the School began as a Regular Member in 1948 and was followed by her appointment to the staff of the recently reopened excavations in the Athenian Agora. Within two years, she produced a catalog of the portrait sculpture from the excavation—her dissertation—which became the first in the long and distinguished series of Athenian Agora volumes. That was the beginning of a half century of scholarly output, which often took material from the Agora as a point of departure, but extended well beyond it. In 1951 she accepted a faculty position at the University of Cincinnati. This was the first of a series of distinguished teaching posts—followed by positions at Columbia, Princeton, and more than 30 years at the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU—which formed the other branch of her twin interests in research and teaching. With the rare exception of sabbatical years, it also set the pattern by which she would spend the rest of her life: the academic year at her home institution and the summer in Athens at the School. At each university, she gained graduate students, and these students usually followed her to the School, often becoming recognized scholars in their own right. These were not her only students, however, for Eve was a born teacher. In Athens, she was frequently asked to lecture at the National Museum, where anyone lucky enough to hear about it was usually welcome to join. In this way, many individuals learned from her how to look intensely, and then to look again. Not all teaching took place in such a formal setting, however. Nearly every day in Athens, she worked in the Agora apotheke and would invite students or colleagues to join her there if she thought material from the excavations, of which she had an encyclopedic knowledge, would add to their research. Teatime at Loring Hall in the late afternoon was another occasion ripe for education. With her deep knowledge of classical languages and history, she often had astute observations or useful suggestions for students in areas of study far removed from her own specialty. When international scholars came to call, she made sure to introduce them to students whose own scholarly interests might overlap with theirs. She eventually spent time with every major collection of ancient art in the world and continued to teach well into her 80s, but she always returned to Athens. She based herself in the storerooms of the Stoa of Attalos or the Blegen Library, where she wrote her famous articles, joined students and colleagues for tea or ouzo on the terrace at the end of the day, and always stayed in a room at the School. The American School was her true home, the constant in her life, and she always sang its praises.

It would please Eve to know that living quarters for both students and senior scholars have been upgraded and expanded so that the School can better accommodate its members, allowing them to focus on their work without the distractions of daily life—not only a place to rest their heads, but also spaces where less formal but often illuminating conversations take place, thoughts are shared, and even ideas are born. It is likewise fitting that Eve herself be remembered as a person who contributed significantly to our knowledge of the ancient Greeks and to the education of others striving to do the same.

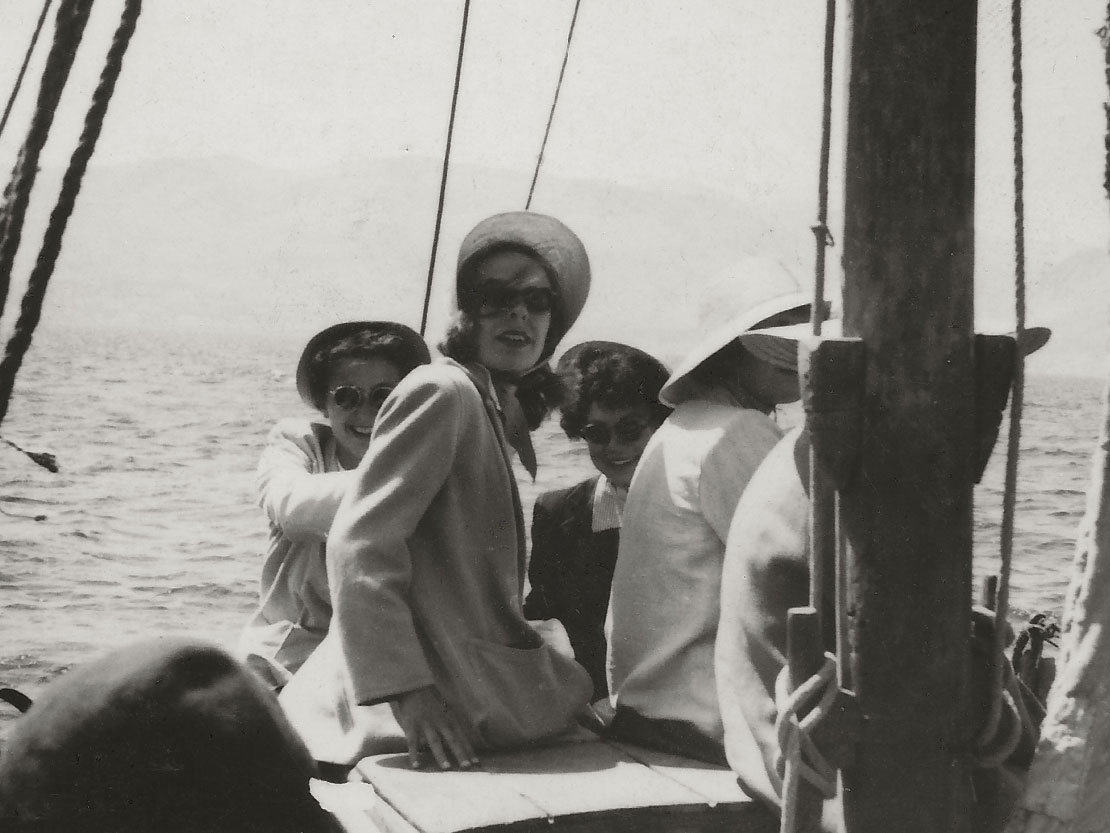

| Eve Harrison (second from left) with two of her fellow students. Inscribed on back, in her hand: Anna [Benjamin], Evelyn [Smithson], and me on caïque between Cheshme and Chios (Chios in background), June 12, 1949 (photo courtesy of Evelyn B. Harrison Photo Collection) |

Elizabeth Milleker, former Associate Curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was a student of Harrison’s at the Institute of Fine Arts: “Eve fulfilled her responsibilities as an adviser in an exemplary way. She was always in her office when you came, returned papers on time, offered advice about scholarships and jobs, and sent letters of recommendation promptly. In one case, she even went to a necessary face-to-face interview for a student who was overseas. When the all-male committee said that it would be silly to give the girl a fellowship as she would surely marry, Eve simply sat there and looked at them until the penny dropped and they awarded the fellowship.”

“Her lectures gave us her findings, but it was primarily in the museum that she taught us to see. Armed with a flashlight, she gathered us close around each marble statue. She seemed to approach each work as though for the first time. No detail was too small or insignificant—the size of crystals, tool marks and style of carving, the stance, the drapery, the hair, the attributes. She worked like an Athenian painter, who always drew the body first and then dressed it.”

“Eve’s interpretations were sometimes worked out with her students. She gave seminars on the problems at hand and quietly took notes while each student gave a report. One day I found her moving around her office with a large pole, trying to recall exactly how she had poled a raft through shallow waters in her youth. She explained she was toying with the idea that the arm position of one of the wounded Amazons meant that she had been poling through the swamps to safety at Ephesus. We poled around the room for quite a while.”

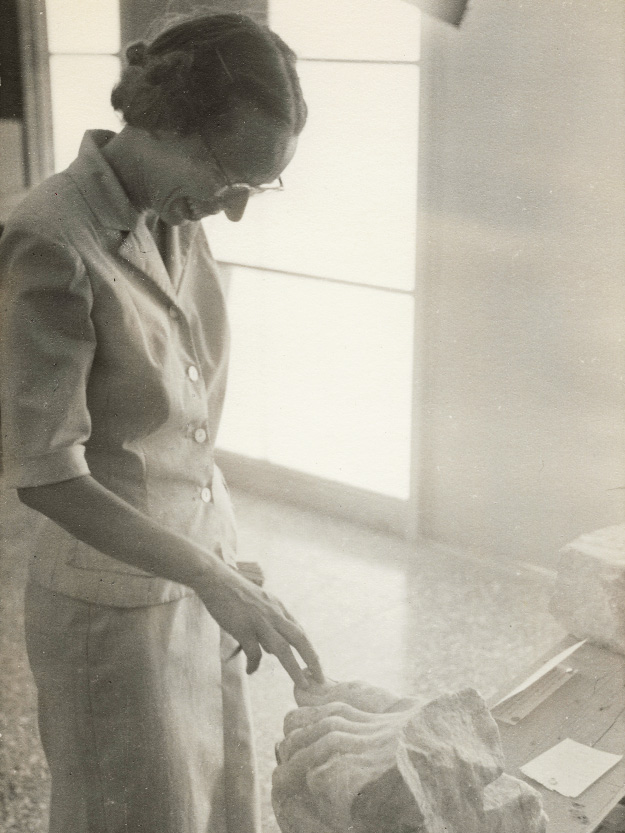

| Eve Harrison as a young scholar in the Agora Museum offices (photo courtesy of Evelyn B. Harrison Photo Collection) |

Olga Palagia, Professor of Classical Archaeology Emerita at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, recalls, “I first met Eve in the Agora in summer 1971 when I was an undergraduate at Athens University. I was deeply impressed by her profound knowledge of Greek sculpture and her willingness to share her insights with students and younger colleagues. She had the great advantage of being associated with an excavation where she acquired intimate knowledge of the sculptural finds as they came out of the ground, and she always insisted on autopsy before publication.”

“I am grateful for all the things she taught me, particularly how to pay attention both to the marble a sculpture is made of and to its technique, for these details help decipher questions of date and provenance. I was privileged to edit her chapter on Pheidias in Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture (edited by J. J. Pollitt and me, Cambridge 1996) and to present an assessment of her achievements when she received an honorary degree from Athens University in 1995. Many of her ideas on the sculpture of Athens, the Nike temple, and Pheidias’ Athena Parthenos, in particular, have stood the test of time, and I find myself happily citing her again and again.”

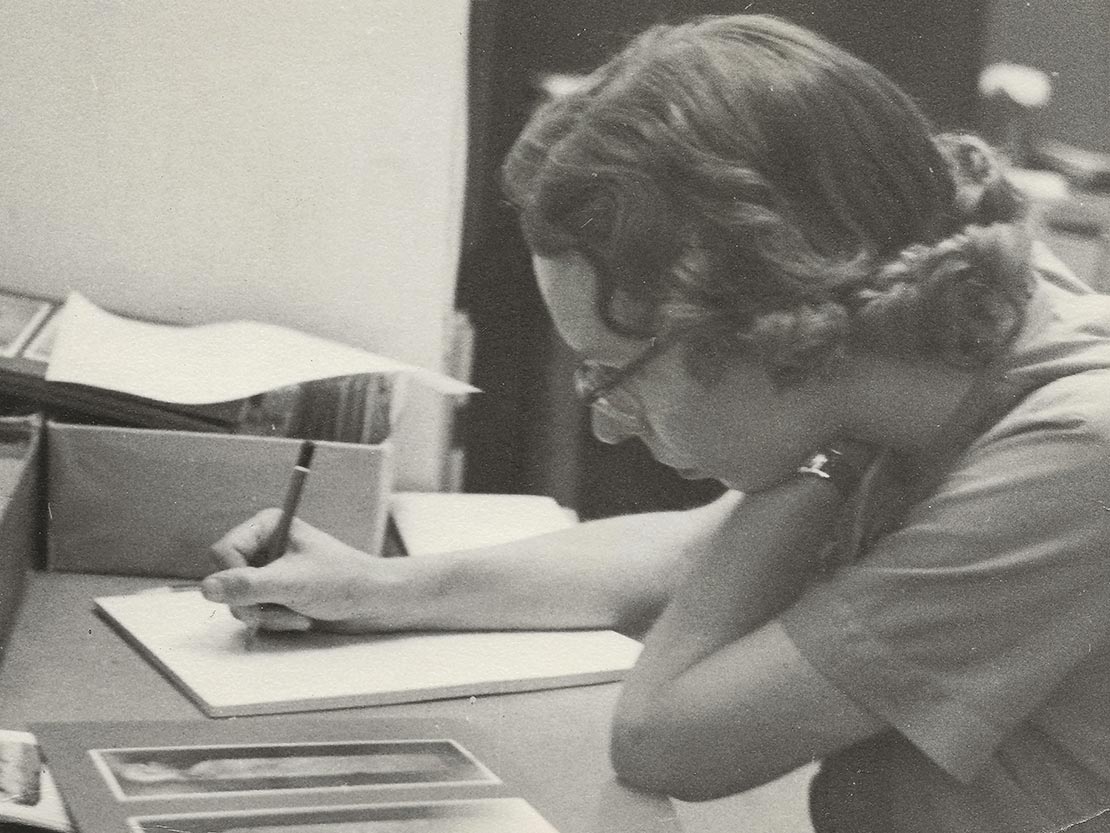

| Eve Harrison drawing from photos of a herm, Agora Records Room (photo courtesy of Evelyn B. Harrison Photo Collection) |

Alan Shapiro, W. H. Collins Vickers Professor of Archaeology Emeritus and Academy Professor at Johns Hopkins University and honorary co-chair of the School’s Edward Capps Society, remarks, “Eve Harrison’s seminars at Princeton were the most challenging I experienced in my graduate career. During the first half of the semester, before students were ready to give their reports, she spoke for the entire three hours (with a break), and there was little or no question period or discussion. These presentations were tours de force of careful organization, delivered in a slow, steady voice with an economy of slides. Typically, she would present an article that was in the works or about to appear in print. The one I remember most vividly was not on sculpture, the subject for which she was best known. On the first day of this seminar in the fall of 1972, she had spoken of what today might be called an ‘iconographical turn,’ moving away from studies of style and connoisseurship to the interpretation of monuments, including vases. The paper in question was published later that fall in the Art Bulletin, under the title ‘Preparations for Marathon, The Niobid Painter, and Herodotus.’ The vase at the heart of the paper, one of the most enigmatic in red-figure, led her into an investigation of the iconography of the ten Eponymous Heroes, a subject to which she would return in several more papers. The argument was subtle, extremely learned, and difficult to follow. At one point, I made the mistake of taking my eyes off the slide (which had been up for about 20 minutes) and looking at her, in a desperate attempt to follow her train of thought. Without missing a beat, she said, ‘I’m sorry if you’re bored, Mr. Shapiro,’ as I quietly sank into the floor. I never made that mistake again.”

| Eve Harrison, 1954 (photo courtesy of John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation) |

Carol Lawton, Ottilia Buerger Professor of Classical Studies Emerita at Lawrence University, said, “Eve was, of course, one of the preeminent scholars of ancient Greek art, especially of the sculptors and sculpture of the Athenian Akropolis and the Agora. She could be formidable, even intimidating, with her extraordinary command of the field and her high expectations of her students, but at the same time she was also encouraging, thoughtful, and kind. Having gone to Princeton to study with her, I was naturally very disappointed when she soon left for the Institute of Fine Arts, but she kept in touch with me and encouraged me to explore the sculpture from the Agora, where I ultimately learned more from her example than I ever could have from lectures in the classroom. There, with her keen eye, she modeled the importance of close, first-hand examination and of all that could be extracted from even the most poorly preserved fragment of sculpture before turning to its meaning and context.”

“I will be eternally grateful that she gave me the opportunity to publish the Agora votive reliefs (almost one-third of which she had rescued from marble piles on the site) and the Agora dedications to the Mother of the Gods (with her characteristic generosity, sharing with me her copious notes on the subject).”

| Eve Harrison studying joined foot from monumental statue, Agora Museum, 1959 (photo courtesy of ASCSA Archives, Homer A. Thompson Papers) |

Betsy Pemberton, who was Harrison’s student at Columbia, added, “Above all, Eve taught me how to see, not just to look at a pot or statue, but to really see it, slowly, carefully, patiently analyzing the characteristics and thinking before coming up with a hasty interpretation. In Greek, the verb oida (I know) is the perfect tense of the verb eido (I see). And this is what Eve taught her students. Seeing leads to knowing or at least to a supportable interpretation.”

| T. Leslie Shear Jr., Eve Harrison, and John Camp examining a Roman bust excavated by Camp from a well on the slopes of the Areopagus in Athens, 1971 (photo courtesy of the Agora Excavations, ASCSA) |

Theodosia Stefanidou-Tiveriou, Professor Emerita of Classical Archaeology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, recalled, “In the 1970s, I met Evelyn Harrisοn when I was writing my doctoral dissertation on the Amazonomachy reliefs on the shield of Athena Parthenos by Pheidias. Even though I was a student, she treated me as an equal. When I told her that I did not have anything significant to contribute to the reconstruction of the shield’s composition except for some additional details, she responded: ‘In scholarship, details make a difference!’”

“Harrison’s important contributions to the study of archaic and classical Greek sculpture and, in particular Athenian sculpture, are well known. But I also wish to highlight her contribution to the study of portrait sculpture of the Roman period. Her volume The Athenian Agora (Volume I): Portrait Sculpture was one of the earliest attempts to study portraiture in the Roman provinces. It is not simply a catalog of portraits found in the Agora. Both in the individual entries and the lengthy Introduction, the young scholar demonstrated to the academic community a multifaceted approach to the study of the Roman portraits of Athens which remains valid to this day. In this field, too, Evelyn Harrison was a pioneer.”

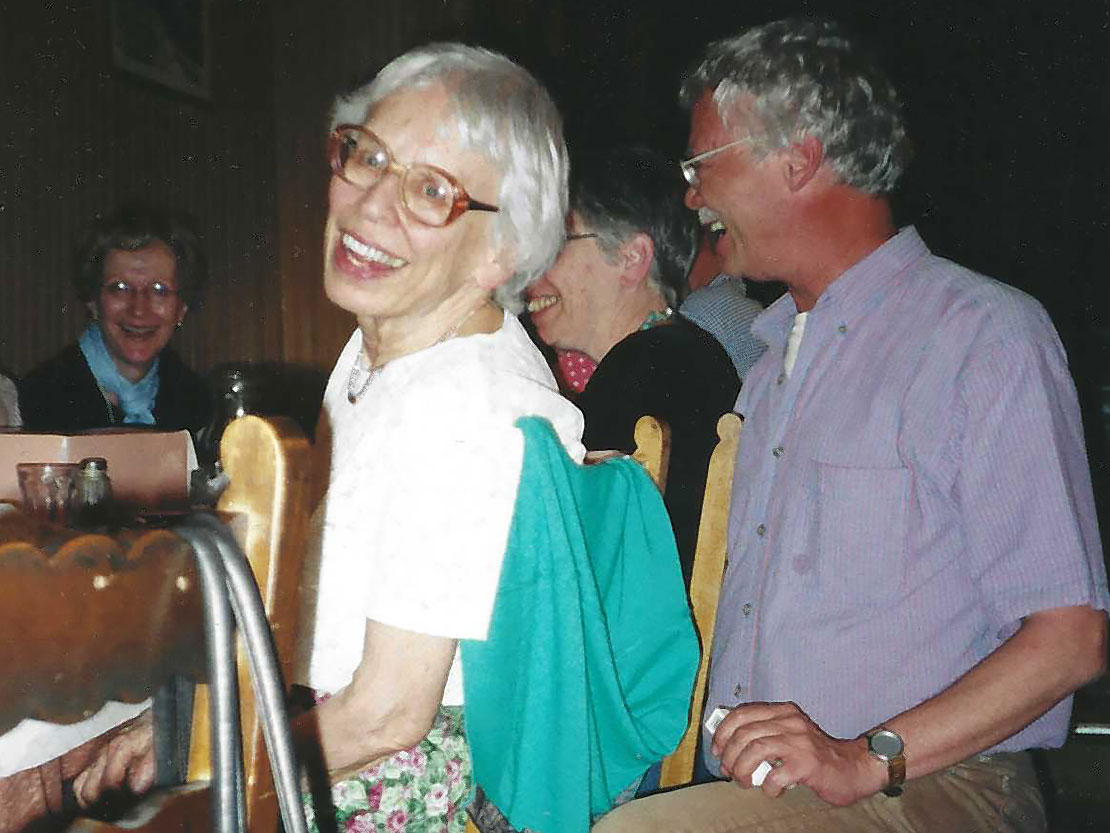

| Caroline Houser, Jenifer Neils, Barbara Tsakirgis, and Marjorie Venit performing their Homeric Hymn to Pallas Evelyna, “glorious teacher, grey-eyed and ethically true,” during Harrison’s 80th birthday party in the School garden on June 14, 2000 (photo courtesy of ASCSA Archives) |

Jenifer Neils, Director of the American School, said, “Eve was a fixture nearly every summer at the American School, where our summer sessions would have been incomplete if she had not taken our students to the old Acropolis and/or National Museum. Her stature was in no way diminished—even by the Sounion Kouros, whose primary place in archaic Greek chronology she helped to establish.”

“Eve’s first work in Athens resulted in a seminal study of ancient portraiture, which she summed up in her characteristic way as follows: ‘The excavations of the Agora have yielded many fine portraits: original marble heads, herms and busts of men and women whose names are rarely known to us but whose faces, expressive, individual, and sometimes even beautiful, give us a vivid sense of nearness to the ancient world.’ And this sums up Eve’s extraordinary gift to us—a vivid sense of nearness to the ancient world.”

| Eve Harrison (far left) taking part in a goat roast, an iconic communal activity in Greece (photo courtesy of Evelyn B. Harrison Photo Collection) |

Janet Burnett Grossman, Regular Member (Fall 1991), who went on to become a curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum, adds, “Miss Harrison was responsible for my becoming a scholar of ancient Greek sculpture. When I entered the Institute of Fine Arts in Fall 1987, I thought that I wanted to study Greek vases. But it was my good fortune to take Miss Harrison’s Greek sculpture class in the first semester. I fell under her sway, and she saw scholarly potential in me before I was cognizant of any. She became my mentor and was the person who encouraged me to undertake the study and publication of the funerary sculptures that had been discovered in the Athenian Agora.”

| Caroline Houser, Eve Harrison, and Sheila Dillon in Loring Hall's Saloni, ca. 1990s (photo courtesy of Sheila Dillon) |

Sheila Dillon, Chair and Professor of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke University, said, “Although I ended up writing my dissertation with Bert Smith, Evelyn Harrison was the reason I applied to study at the Institute of Fine Arts. I took my very first graduate seminar with her, on the Parthenon frieze, an experience I can still recall with great clarity. Ms. Harrison was a teacher and a mentor both at the Institute and in Athens at the American School, where I had the great fortune to hear her talk about Greek sculpture directly in front of the objects themselves. She was always encouraging and supportive of me and of my work, which was a tremendous source of confidence particularly during my first years in graduate school, as she surely must have known how little I knew—one thing you could never hide from Eve was your ignorance. But she clearly must have seen some hint of potential in me even then, and for that I shall always be grateful. While I will never command the breadth of her knowledge or approach the level of her intellect, I hope I can impart to my own students some of the things that she taught me: to look closely and with care, to pay attention to small details, to love fragments, to take style seriously, and to write clearly and precisely but also vividly.”

Randy Harrison, Evelyn Harrison’s nephew, reflected, “Eve, or Ewee as her family knew her, took a keen interest in her family, consistently demonstrating her loyalty and love. Ewee inspired us with her unwavering commitment to excellence along with her sense of dignity and her gracious demeanor.”

EXCERPT FROM THE 1992 AIA GOLD MEDAL TRIBUTE

“Eve Harrison’s scholarship has redefined our art historical perception of the fifth century. As her studies of Alkamenes and Phidias have sharpened our understanding of personal style, so her analysis of Archaic and Classical sculpture has refined our knowledge of period style. Her provocative reconstructions of lost originals—from the shield of Athena Parthenos to the cult statue of the Hephaisteion—have urged us to view all monuments with an acute awareness of their archaeological, cultural, and historical context. Her examination of dress and of coiffure has demonstrated to us the interrelationship of style and iconography. Her approach has extended our knowledge of Classical art beyond its aesthetic and intellectual achievement to an appreciation of its place in the continuum of cultural expression. The single monument that has most benefited from Eve Harrison’s attention is the Parthenon. She has written nine articles on its sculpture: one on the metopes, two on the frieze, three on the pediments, two on the shield of Athena Parthenos, and one on the Nike she held on her hand. Eve Harrison’s examination of the sculpture of the Parthenon, and of the Nike Temple too, reminds us that monuments are most illuminating when considered within their social and historical context.”

EVELYN HARRISON’S AWARDS AND HONORS

Throughout her illustrious career, Evelyn Harrison received a number of prestigious awards and honors for her contributions to art history and archaeology, including:

- Guggenheim Fellow (1954)

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1973)

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (1979)

- Corresponding Member of the German Archaeological Institute

- Archaeological Institute of America’s Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement (1992)

- Honorary Degree from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (1995)

- Honorary Councilor of the Archaeological Society of Athens

EVELYN HARRISON’S 80TH BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION IN ATHENS

In June 2000, Eve’s 80th birthday was celebrated in Athens with a series of events, including a rooftop party with colleagues, a grand reception in the American School gardens, and a celebratory dinner.

| Charles Williams, Nancy Winter, and Eve Harrison |

| Presentation of birthday gifts by Caroline Houser (right) |

| Iannis Akamatis, Eve Harrison, and Jim McCredie in the School gardens (photo courtesy of Linda Roccos) |

| 80th birthday dinner at a taverna: Caroline Houser, Eve Harrison, Marjorie Venit, Bob Bridges, and many others |

TRIBUTE TO EVELYN HARRISON

Following her death, Jim McCredie, life-long colleague and fellow American School stalwart, paid tribute to Eve Harrison with an astute and moving summation of her life and work, published in the American Journal of Archaeology in July 2013. We reprint it here in full.

Evelyn Byrd Harrison was born June 5, 1920, in Charlottesville, Virginia, and graduated from John Marshall High School in Richmond. She was descended from two First Families of Virginia, lineages recognized as belonging among the first wave of English settlers to colonize Jamestown in the 17th century. The Byrds became a lasting and prominent political dynasty in Virginia, as did the Harrisons, who produced Virginia governors and two American presidents. As a southerner, Harrison was proud of her family heritage, which even boasted distant kinship to Pocahontas, but her life and her life’s work was spent in other places. She came north for her education, receiving her A.B. from Barnard College in 1941 and completing her M.A. at Columbia University in 1943. She then had a break in her studies. Like many of her peers, she was enlisted in the war effort, serving as a Research Analytic Specialist until 1945, where she worked on encryption and code breaking. Believing that as a classicist she had superior language skills, the army gave her a crash course in Japanese and then set her to translating intercepted Japanese messages for the War Department.

By 1946, she had resumed doctoral studies at Columbia, studying with William Bell Dinsmoor and Margarete Bieber, and in 1949 she joined the staff of the excavations of the Athenian Agora conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Her dissertation on the portrait sculpture from the Agora came out of this work. It was revised and published in 1953, the year after she was awarded her Ph.D., under the title Portrait Sculpture. It inaugurated the Agora excavation series. In 1965, Harrison contributed Archaic and Archaistic Sculpture to the series. She wrote in its preface, “[t]he Agora sculpture helps us to understand the everyday background from which the great Athenian sculpture sprang and the working of the tradition which kept these inventions alive for the enjoyment of later ages.” Exploring this interplay was a hallmark of her scholarly output. Both books, which came early in her career, represented important contributions to the history of Greek sculpture and secured her place in the field. Her superb eye, her analytical intellect, and her gifts as a writer abound in these works.

Her teaching career began at the University of Cincinnati in 1951, where in addition to art history she taught first-year Greek and Latin. Between 1953 and 1955, she returned to research at the Agora excavations before joining the faculty of the Department of Art History and Archaeology of Columbia University, where she was named full professor in 1967. Following her time at Columbia, she spent four years at Princeton University; she was the first woman to become full professor in the Department of Art History and Archaeology. In 1974, she joined the faculty of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, as Edith Kitzmiller Professor of the History of Fine Arts. She became professor emerita in 1992 but continued teaching at the institute until 2006.

Throughout her long career, she spent almost every summer at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, studying the material from the Agora and elsewhere. This meant that her unusually sharp eyes were continually honed. She possessed an uncommon visual command of Greek sculpture akin to a mental database that allowed her to readily call up images of everything she had ever seen. This visual acuity, along with her deep and broad knowledge of the ancient world, grounded her scholarly pursuits. Above all, her interest was in iconography, in uncovering and understanding the meaning of sculpture, monuments, and architecture, especially within the context of fifth-century Greece, although her publications ranged from the Daedalic period to the age of Constantine. She was a master of using details, often from fragments, to point to a deeper understanding of Greek history, culture, and society. The questions she posed were basic. For example, she wanted to know who was being represented, what story or myth was being told, why it was being told in a certain way at a certain time, and how that ultimately fit into the larger scheme of life during that period. In Athens, she taught generations of students in excavations and museums. No one was more inspiring in front of ancient sculpture.

Her research as an art historian always proceeded first from the object. She began by intensely looking at and examining what she was studying and from there proceeded into close analysis. She possessed a phenomenal capacity to analyze style. In particular, her contributions to style analyses of costume, including hair and dress, down to details such as how particular folds draped, played an important role in suggesting dates for sculpture and monuments and placing them into an overall fifth-century chronology, a period in which few securely dated pieces exist.

Equally important, she translated her research and hypotheses into books and articles that were admired for their well thought out, methodical arguments and their precise language. Her writing also evoked her empathetic connection to the ancient world and its inhabitants. For example, her description of a marble miniature of Julia Domna brings the sculpture to life: “Expressive eyes and mobile mouth convey the vivid personality of the Syrian-born empress, to whom the Athenians gave divine honors.” And the sculptural quality of Athena’s hair evokes much more when Harrison suggests “[w]e are tempted to recall that Athena’s birthday was in midsummer, when the strong north wind stirs up the Aegean in just such lively waves.”

Her years at the Institute of Fine Arts were prolific. She published numerous articles, including an important three-part series “Alkamenes’ Sculptures for the Hephaisteion.” These years were also devoted to teaching as well as mentoring her Ph.D. students. She was very discriminating in the doctoral candidates she took on, choosing them not only for their talent but also for the potential she saw in them. Often, she could discern the direction of their interests before they did, and she was extremely skillful in assigning research topics that well suited them. As a mentor, she tended to teach by listening, guiding, and showing, rather than telling. For instance, she might suggest, then demonstrate how a particular fragment fit into a sculpture, something that could be difficult for those in training to see at first. And she was always generous with her time, making herself available to talk through questions and problems. In fact, an afternoon conversation with her could last an hour or much longer and range over the entire ancient world, from sculpture to politics to literature. She was famous for her erudition, which spanned the ancient world. If a point of interest arose that she was not familiar with, her own deep sense of curiosity would propel her to investigate it for herself.

Outwardly she possessed a courtly southern manner and always had a ready smile, but immediately underneath this gracious exterior was the force of her fierce intellect. She could be intimidating, yet she was also deeply admired, especially by her students. On a day-to-day basis they witnessed her commitment to teaching and to scholarship. As “Miss Harrison students” they experienced her loyalty in supporting them through their degrees and into the next phases of their careers. She was unfailingly helpful, not only as a teacher but in practical matters, too, such as steering them toward appropriate fellowship opportunities and advocating that they receive fair pay for their work, including student jobs.

As an éminence grise in the field of Greek sculpture, Harrison was among a small group of noted experts asked to give their professional opinions when the J. Paul Getty Museum was in the process of acquiring a controversial kouros. Was it right or not? Was it a fake? Ultimately, the conclusion would rely heavily on the trained eyes of this small cadre of experts. On seeing the kouros, Harrison’s immediate response was subdued and unequivocal. She simply indicated that she was sorry to hear the Getty was about to complete the purchase of the statue. Somewhat surprisingly, the story of her role in the Getty kouros controversy crossed into the realm of popular culture when it was featured in [Malcolm] Gladwell’s book Blink: the Power of Thinking Without Thinking. It served as the lead-in case study setting up the book’s premise that first impressions are generally right because they are based on a surfeit of underlying experience and knowledge that merge into instant judgments that are usually intuitively sound. Harrison's immediate and assured response to the questionable Getty kouros beautifully demonstrated Gladwell’s hypothesis. At the same time, this story does not begin to do justice to the depth of her scholarship and accomplishments, which yielded her profound knowledge of ancient Greek sculpture. Her reaction to the Getty kouros was prefigured some 40 years earlier when she wrote of a particular image, “our plates appear distressingly different from those of a museum catalogue. One does not see by a glance at Plate 1 that the fragments shown there belong to a kouros better than the one in New York. One learns it by studying.”

Her distinction, long recognized by her students and colleagues, was publicly marked by election to the American Philosophical Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, and by an honorary degree from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. She bore these honors, and others, lightly. After a long and distinguished career, she was awarded the Archaeological Institute of America’s Gold Medal for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement in 1992. She brought immense gifts to her profession as an art historian that combined with her commitment to scholarship to ensure she played a significant role in shaping the course of classical art history during the second half of the 20th century, one that deepened our understanding of individual works of art and broadened our awareness their archaeological, cultural, and historical context. Evelyn Byrd Harrison died peacefully at home in New York on November 3, 2012.

Source: McCredie, James R. “Evelyn Byrd Harrison, 1920–2012.” American Journal of Archaeology 117, no. 3 (July 2013). ajaonline.org/online-necrology/1605.

ABOUT THE STUDENT CENTER CAMPAIGN

The Student Center Campaign was launched in October 2018 to raise funds for renovating and expanding the three aging buildings that serve as the intellectual and residential heart of the American School: Loring Hall, the Annex, and West House. This transformative project will increase housing capacity, reduce energy consumption, add state-of-the-art features and technology, and bring the buildings up to the latest technical standards—all while preserving the complex’s historical appearance. The Student Center will remain the place where members of the community gather for meals, tea, ouzo hour, holiday celebrations, and lectures—a source of lifelong professional and personal relationships that characterize the collegial and intellectually vibrant atmosphere of the School. This modernized setting will enhance that experience and will meet the needs of the School community well into the future.

SUPPORT THE CAMPAIGN

The goal of the Student Center campaign is $9.4 million, inclusive of a maintenance endowment. Thanks to generous supporters like the Students and Friends of Evelyn Harrison, $7.7 million has been raised to date. The new Student Center is expected to open in June 2021.

To learn more about how you can support this historic initiative, please contact Nancy Savaides, Director of Stewardship and Engagement, at nsavaides@ascsa.org or 609-454-6810. Naming opportunities for a variety of spaces in the Student Center are still available. Donors can choose from a wide range of gift levels to name a room or area in honor of themselves, an American School scholar, or a family member, friend, or group. Please click the links below to view the nameable spaces and options that remain:

STUDENT CENTER CONSTRUCTION PHOTO GALLERY

Click this link to view more photographs of the work in progress.