Ancient Selfies: Potters at Work on the Penteskouphia Pinakes

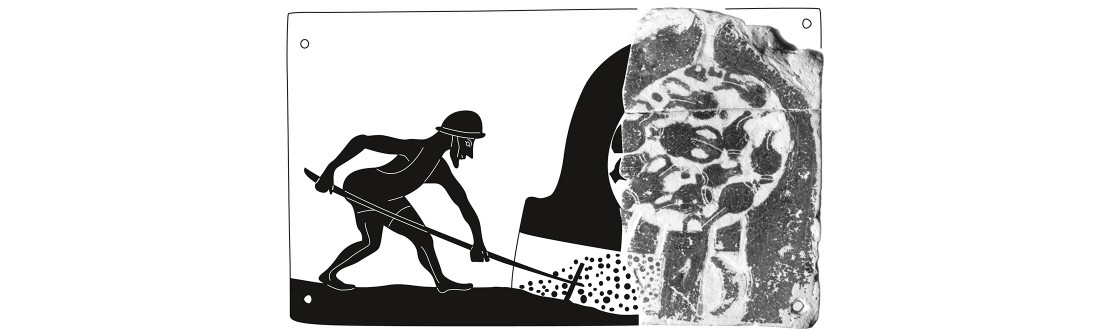

Eleni Hasaki’s new book in the Hesperia Supplement series, Potters at Work in Ancient Corinth: Industry, Religion, and the Penteskouphia Pinakes, presents a contextualized examination of the many scenes of potters and painters at work within the unique assemblage of painted clay pinakes, or plaques, unearthed at this otherwise obscure site southwest of Corinth in the late 19th century. While individual Penteskouphia pinakes are well known as frequent illustrations in works on ancient crafts and craftspeople, the corpus as a whole has remained enigmatic, not least because of the practical difficulties of studying 1,200 fragments dispersed in museum collections in Berlin, Paris, and Corinth. Accompanied by a comprehensive register of all these fragments, Hasaki’s authoritative study of the nearly 100 pinakes with images of potters at work places these scenes within their wider artistic and societal context, including discussions of the technology involved in pottery production, the relationship between Corinthian and Athenian art, and the economic and religious anxiety of Corinthian potters in the 6th century B.C. Made by the potters themselves in their own medium, these images are the closest thing we have to ancient selfies!

Eleni Hasaki’s new book in the Hesperia Supplement series, Potters at Work in Ancient Corinth: Industry, Religion, and the Penteskouphia Pinakes, presents a contextualized examination of the many scenes of potters and painters at work within the unique assemblage of painted clay pinakes, or plaques, unearthed at this otherwise obscure site southwest of Corinth in the late 19th century. While individual Penteskouphia pinakes are well known as frequent illustrations in works on ancient crafts and craftspeople, the corpus as a whole has remained enigmatic, not least because of the practical difficulties of studying 1,200 fragments dispersed in museum collections in Berlin, Paris, and Corinth. Accompanied by a comprehensive register of all these fragments, Hasaki’s authoritative study of the nearly 100 pinakes with images of potters at work places these scenes within their wider artistic and societal context, including discussions of the technology involved in pottery production, the relationship between Corinthian and Athenian art, and the economic and religious anxiety of Corinthian potters in the 6th century B.C. Made by the potters themselves in their own medium, these images are the closest thing we have to ancient selfies!

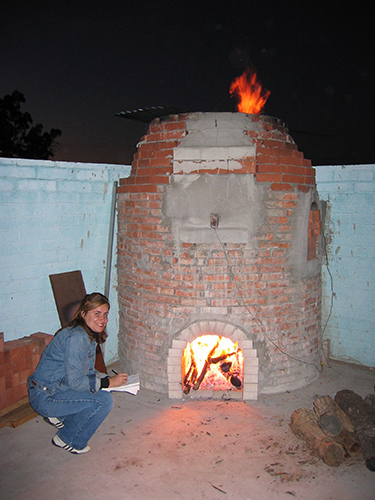

Eleni Hasaki with her new book on display beside modern pinakes fired in the replica Greek kiln constructed by the AIA Tucson chapter

(Photo M. Serino; pinakes by T. Schreiber and E. Hasaki; kiln construction coordinators A. May and E. Hasaki)

Hasaki’s relationship with the Penteskouphia pinakes began in graduate school. “In the early years of looking for a dissertation topic,” she recalls, “I had focused on representations of artisans before turning to the more tangible remains of archaeological evidence of ceramic workshops, especially the kilns.” Her 2001 dissertation included an appendix on the Penteskouphia pinakes based on published information, but she recognized then that the corpus deserved a lengthier treatment. In 2006 she visited the Antikensammlung in Berlin for the first time—where the largest collection of Penteskouphia pinakes is held—and would return for further study several times over the next decade, in addition to study at the Corinth Museum and the Louvre in Paris. While the scenes with potters at work were always her focus, this holistic autopsy was crucial both in illuminating those images and in identifying wider patterns. “In order to underscore that these depictions are a rarity within the assemblage,” Hasaki explains, “I had to look at the wider corpus. Sometimes being very familiar with one theme, like a worker climbing the walls of a kiln, allowed me to correctly identify other scenes previously misidentified as ‘dancers,’ for example. Having a panoramic view of the assemblage facilitated finding iconographic parallels for scenes or details and noticing production marks on the back sides or thin edges. In the end, stepping back from this small portion of the assemblage (about 8%) made me appreciate both the part and the whole!”

![]()

Distribution of themes on one- and two-sided Penteskouphia pinakes (E. Hasaki)

Hasaki’s larger research interests relating to pottery production and kiln technology were also vital in her study of the pinakes, since the bulk of the scenes of potters at work depict kiln firings. Her multi-faceted approach to understanding ancient kilns through iconographic, archaeological, experimental, and ethnoarchaeological evidence has included a project to construct and fire a replica Greek kiln with the Tucson chapter of the Archaeological Institute of America (https://aiagreekkiln.arizona.edu) and a project studying traditional potters’ communities in Tunisia, where she observed several night firings. These experiences, Hasaki notes, helped her “decode” the scenes on the pinakes more deeply, underlining “the importance of the color reading for the flames against a night sky, for example, or the importance of the kiln master—often the master potter of the workshop—stacking the lower foundational layers of a kiln.”

Eleni Hasaki takes notes during a night firing of the replica Greek kiln constructed by the AIA Tucson chapter, 2005

(Photo AIA Ancient Greek Kiln Project)

The prevalence of kiln firing scenes is one of the aspects that distinguishes the Penteskouphia images of and by Corinthian potters from Athenian depictions of craft production. Attic vase painters showed potters at the wheel, either forming vessels or painting them, but tended to depict other crafts more often than their own. “Only from Corinth do we have such a large assemblage of industrial iconography,” Hasaki emphasizes, and “this rich Corinthian iconography counterbalances the dearth of Corinthian potters’ signatures (only three individuals are named).” She describes the significance of the kiln firing scenes to the Corinthian potters:

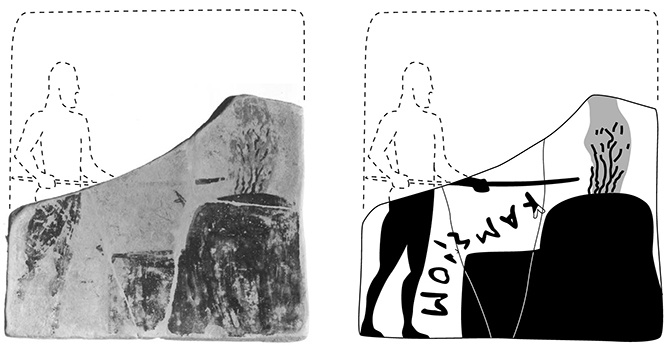

The firing was the final quality check of the cumulative experience of the entire workshop: from the workmen treading the clay, to the potter forming, to the sharp eye of the worker monitoring the drying of the pots, to the careful stacking of the kiln, and the gradual firing and cooling of the kiln load. The focus of the Corinthian potters on this stage matches the anxiety of the Athenian poem entitled Kaminos (Kiln) that featured for the first and only time in Greek literature the five kiln demons, including “Smasher,” “Crasher,” and “Shake-to-Pieces” that could at any moment of indifference destroy a kiln load.

When asked if she has a favorite pinax among the Penteskouphia corpus, Hasaki points to the single pinax with an inscription labeling the kiln with its ancient term κάμινος, adding jokingly that she would have liked it to include a signature as well, so that we could say, “this is Milonidas’s kiln!” Even without a signature, though, this pinax speaks to the humanity and intimacy captured in these objects. “What always intrigued me and made these pinakes so immediate,” Hasaki remarks, “is that they come from the hands of potters themselves, made in their workshops, using their basic material and basic skills, and depicting their everyday working environment. Almost like a visual blog of their daily lives.”

Photo and reconstruction drawing of Penteskouphia pinax with inscription labeling kiln as κάμινος

(Berlin, Antikensammlung F 482 + F 627 + F 943 + fr.; photo courtesy Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; drawing Y. Nakas)

Building on this glimpse into the everyday lives of Corinthian potters, Hasaki hopes that one impact of her book will be a renewed focus on the common human anxieties and emotions that connect ancient and modern communities. Given the extraordinary events of the years she spent working on the book, from the financial crisis of 2008 to the current global health crisis, “it is no wonder,” Hasaki reflects, “that I highlighted the economic downturn of the Corinthian industry and that I see in these pinakes both a celebration of the craft and also a concern for its economic viability. Every scholar is a product of their time, and with my double identity as a Greek native and as a US citizen, it is hard not to carry some of these preoccupations into my research.” She hopes that her work may encourage other scholars to “delve a bit more deeply into the hidden fears that people of all times, including antiquity, express about their future, and how humanity connects us all,” continuing,

I was deeply touched by the oracular questions of ordinary people, including craftspeople, on lead tablets in the Sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, “Will I have offspring, and will they survive?” “Should I seek employment in another city?” “Should I continue the profession of my father?” Ceramic industries were no different: workers had to earn their livelihood and support their families. They were less concerned about creating masterpieces of the sort that modern scholars might pour all their energy into. We should see them as part of their wider societies.

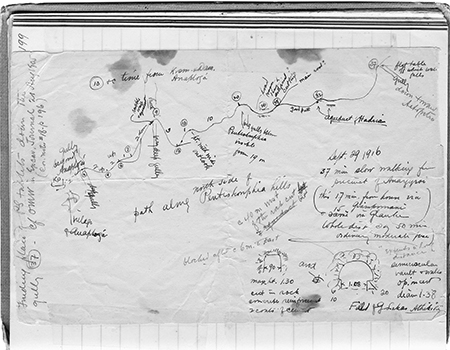

While acknowledging that her book is thus quite personal, Hasaki also emphasizes the collaborative nature of the project and her appreciation for the many colleagues and friends around the world who played a role in its eventual completion. A particularly important collaboration was with Ioulia Tzonou and James Herbst, who contributed a chapter investigating the findspot of the pinakes at Penteskouphia—first in illicit digging in 1879 and subsequently in a re-excavation of the area by the ASCSA in 1905. Hasaki praises Tzonou and Herbst’s contribution as essential, “as it sheds light on the provenance of this looted assemblage, and it populates with people and possibly workshops this rather barren spot of the Corinthian landscape. They worked hard in assembling archival information like Bert H. Hill’s map from 1916 as well as institutional memories from various people (including the recently deceased Ron Stroud, to whom the chapter is dedicated), and brought into the interpretation their immense experience as excavators and interpreters of formative processes.” Another crucial collaboration was with illustrators, especially Yannis Nakas, who drew suggested reconstructions of fragmentary pinakes. Hasaki identifies Nakas’s skills and creativity as crucial in the success of the illustration program. “We went back and forth so many times on how to make the pinakes legible but not overdo the reconstruction,” she recalls, “and I hope in the end we struck a happy medium.”

Bert H. Hill’s map of the area around the findspot of the Penteskouphia pinakes, 1916 (Corinth Notebook 18, p. 199)

Hasaki also collaborated across time, in a sense, with the late Helen Geagan, whose 22-volume archive containing her studies of the Penteskouphia pinakes came into Hasaki’s possession through the generosity of Wendy Thomas as she was finishing the book’s appendices. These appendices compile a massive amount of information about all the known Penteskouphia pinax fragments, including dimensions, epigraphical and chronological information, the iconography on one or both sides, and notes on secure or tentative joins.

Pages from Geagan archives (vol. 19, ca. 1963) proposing a join between pinax fragments in Berlin (F 835) and Corinth (C-1963-450)

Although receiving Geagan’s archive late in the process caused both satisfaction and some struggles with statistics and differing identifications of scenes, Hasaki notes that it also made her “discover the power of the question mark—that we cannot be certain about some scenes or the intention of the potter to cover just one or both sides of a pinax.” She thus hopes that the appendices will be a rich resource for future researchers to expand and correct as they delve into the assemblage and its other themes and patterns. She envisions that one day the entire corpus will be accessible through a searchable online gallery, serving as a springboard for future studies and saving other scholars some legwork. With scholarly attention redirected back to the Penteskouphia assemblage and its comprehensive study, Hasaki also hopes that there may eventually be a survey and/or targeted excavation of this area of Ancient Corinth, to see whether it housed another potters’ community.

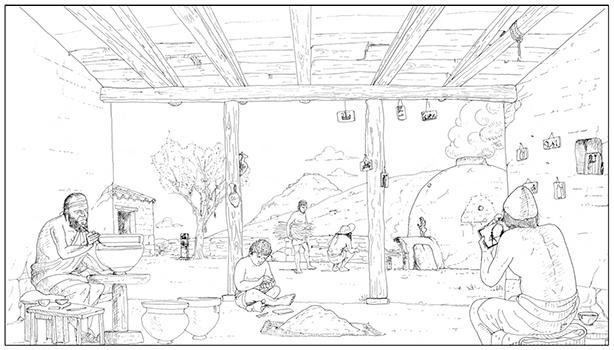

Artist’s rendition of a posited ceramic workshop in the Penteskouphia area (E. Hasaki and Y. Nakas)

As for her own future projects, Hasaki describes “crafts, skills, places, and makers” as the core of her research, so the Corinthian potters of the Penteskouphia pinakes will never be far behind. After the challenges of working with three different collections and hundreds of small artifacts, though, she has chosen to focus her work for a while on one colossal statue in one location, the Nashville Athena Parthenos, in a collaborative project with its sculptor, Alan LeQuire.

As she looks back on her long relationship with the Penteskouphia pinakes and the journey of bringing these ancient selfies to publication, Hasaki remembers an especially motivating artifact of the time before widespread email access, WhatsApp, or modern selfies. “I still hold dear a typewritten note by Mr. Williams [Charles K. Williams II, then Director of the Corinth Excavations] from 1996,” Hasaki reveals, “when I first inquired about whether I could work on the Penteskouphia pinakes. Mr. Williams was a bit cautious, as several previous attempts had not materialized for various reasons. One of my most rewarding moments will be when I have the honor to present the volume to Mr. Williams and share with him this letter, which perhaps most unusually was a source of inspiration and perseverance for me.” We are grateful for Hasaki’s perseverance in bringing these fascinating scenes and their makers to new light in Potters at Work in Ancient Corinth: Industry, Religion, and the Penteskouphia Pinakes.